TEACHER’S GUIDE

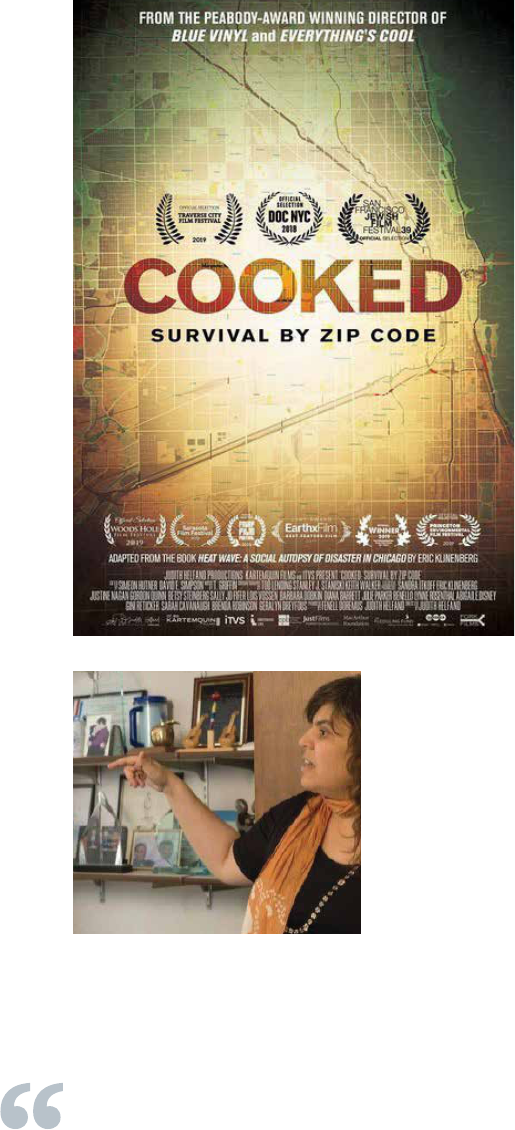

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code

2018 • 54 minutes • Directed by Judith Helfand • Distributed by Bullfrog Films

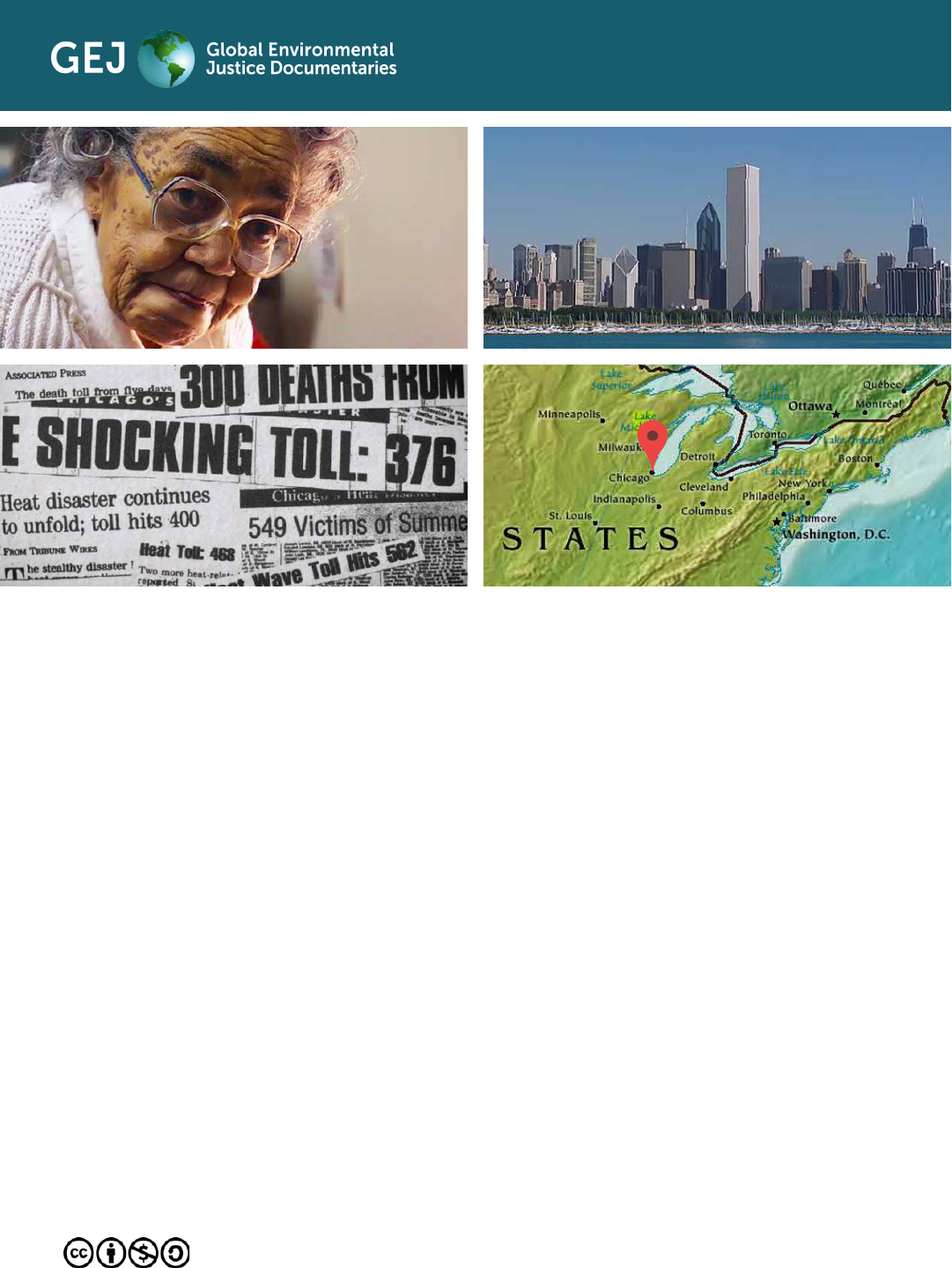

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code is a story about a severe example of environmental injustice and the people most

affected by it. In the summer of 1995, Chicago experienced an unthinkable disaster triggered by extremely high

humidity and a layer of heat-retaining pollution that drove the heat index to more than 126°F (52°C).

Cooked revisits this tragic heat wave in which 739 citizens died over the course of a single week, most of

them poor, elderly, and African American.

Behind the shocking headlines filmmaker Judith Helfand finds a long-term crisis, a “slow-motion disaster”

fueled by poverty, economics, social isolation, and racism.

Viewer advisory: This film includes news footage from 1995 of emergency personnel moving victims in body bags.

Teacher’s Guides may be copied and shared but not sold.

Face to Face Media 2022

CURATOR

Rajashree Ghosh

Affiliated Scholar, Women’s Studies

Research Center, Brandeis University

WHY I SELECTED THIS FILM

Throughout the film Cooked: Survival by Zip Code, filmmaker Judith

Helfand argues that there is an inextricable connection between

environmental injustice and racism as she explores the impact of the

1995 Chicago heat wave that caused hundreds of deaths. The people

most affected, she finds, often live in zip codes that are underserved,

under-resourced, and ill equipped to deal with extreme events like

heat waves, hurricanes, forest fires, and, more recently, pandemics.

An examination of these disasters reveals structural inequalities that

make poor communities and communities of color vulnerable to these

events. The film is an important teaching tool and will promote

critical classroom discussions about how social location, privilege,

and disadvantage intersect to create very different impacts and

experiences within society.

SUGGESTED SUBJECT AREAS

African American Studies Medicine

Environmental Justice Meteorology

Environmental Sciences Political Science

Epidemiology Social Policy

Gerontology Sociology

Management Sciences Urban Economics and Planning

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE FOCUS

The film was inspired by Eric Klinenberg’s book Heat Wave: A Social

Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, which examines the July 1995 heat

wave. Klinenberg and filmmaker Judith Helfand both make the case

for environmental health equity as they point out the damage to

communities inflicted by racially restrictive covenants, redlining by

banks, a lack of safety, exclusion from political engagement in

land-use planning, and inadequate health care, all of which

contribute to a slow-motion environmental and social disaster

created by humans and driven by systemic racism.

SYNOPSIS

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code tells the story of a

tragic heat wave, the most traumatic in U.S. history

at the time, in which 739 citizens died over the

course of a single week, most of them poor, elderly,

and African American.

The film questions existing policy as it explores

a slow-motion disaster that continues to disrupt

and shorten the lives of Chicago residents in

neighborhoods like Englewood, a district ravaged by

pernicious poverty, social isolation, and racism.

This is a place where one resident says, “It’s easier

to buy a gun than a tomato.” One epidemiologist

concludes that 3,200 people die each year from

preventable illnesses in such Chicago

neighborhoods. The filmmaker comes to question

policies that ignore these kinds of ongoing disasters

while preparing, at the same time and at great

expense, for rare events like earthquakes.

The film does find reason to hope for change

because of two community-based initiatives that

address current inequities. Sinai Urban Health

Institute actively reaches out to residents, and an organic farm that

grows vegetables for residents of Englewood calls itself a “human

emergency plan.”

Cooked raises key questions: Can we realign our social priorities?

Can we expand the definition of “disaster” to include socially

patterned deprivation? Would doing so allow us to address the

slow-motion disasters that kill people every day just because they

live in the wrong zip code?

KEY LOCATIONS

Westchester County, New York

Englewood, Chicago, Illinois

Cook County, Illinois

New Madrid Seismic Zone, Tennessee

New Orleans, Louisiana

Paducah, Kentucky

This film is searing,

smart and insightful...

[it] asks important

questions with humor,

humility, and humanity.

This film can be used in

a wide range of

classrooms with social

and ethnic studies and

health policy as well as

in public contexts of

churches, community

groups, and other

venues.

Julie Sze, Professor,

American Studies, UC-Davis

PEOPLE FEATURED

Valerie Brown – granddaughter of Alberta Brown,

who died in the heat wave

Richard Daley – mayor of Chicago from 1989 to 2011

Dr. Edmund Donoghue – chief medical examiner, Cook County

Jim DuPont – President, RescUSA, Illinois Urban Search and Rescue

Maureen Finn – forensic scientist,

Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office

Geraldine Flowers – church elder, Sweet Holy Baptist Church

Oreletta Garmon – community health worker

Shirl Gatling – Gatling’s Chapel and Funeral Services

Judith Helfand – film director

Brigadier General John Heltzel – director,

Kentucky Emergency Management

Sadhu Johnston – chief environmental officer, City of Chicago

Eric Klinenberg – author of Heat Wave:

A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago

Michele Landis Dauber – author of The Sympathetic State

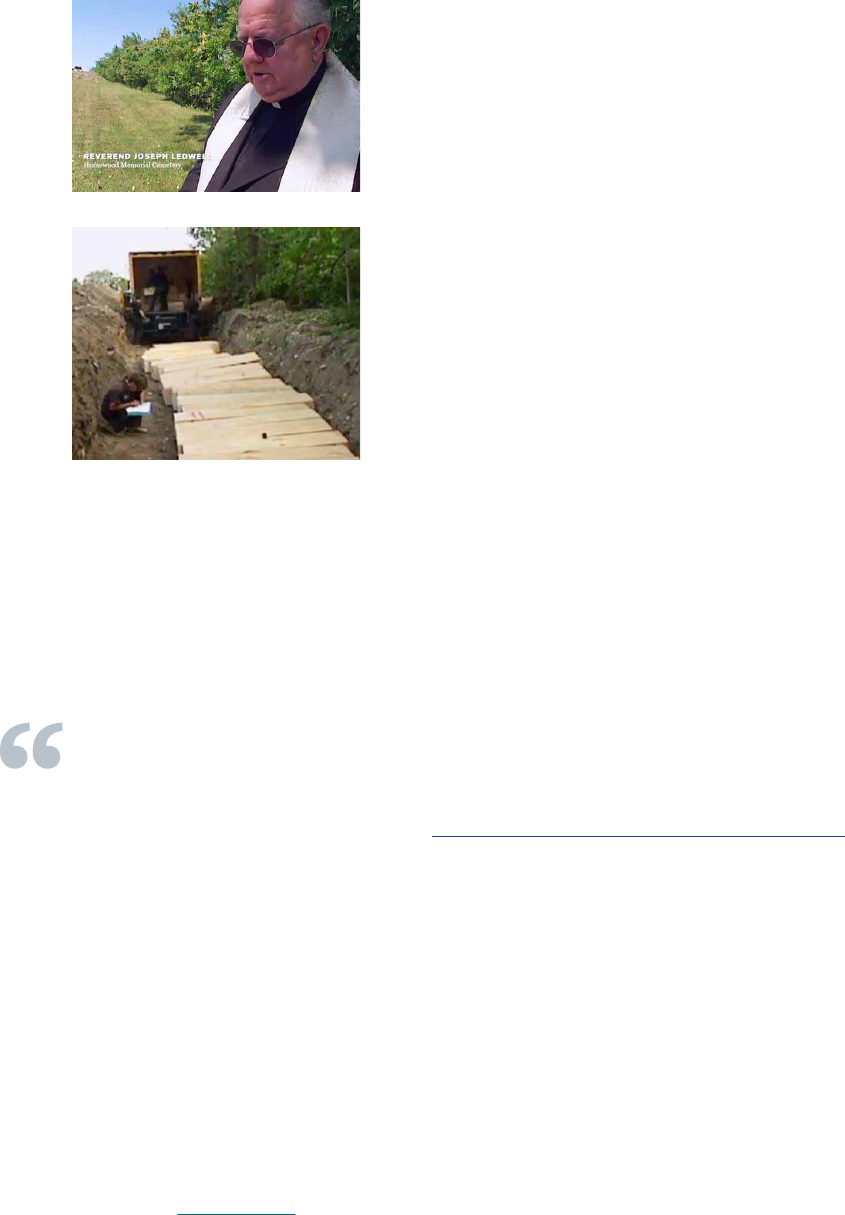

Reverend Joseph Ledwell

Mike McReynolds – medical examiner,

Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office

Dr. Linda Rae Murray – medical officer (ret.),

Cook County Department of Public Health

Andy Nebel – reporter at ABC

Toni Preckwinkle – board president,

Cook County Board of Commissioners

Colleen and Jeremiah Scott – residents of Englewood

Celevia Taylor – community health worker,

Sinai Urban Health Institute

Bessie Trotter – Action Coalition of Englewood

Steve Whitman – chief epidemiologist, City of Chicago

Orrin Williams – community organizer, Englewood, Chicago

Cooked / Global Environmental Justice Documentaries

WHY I SELECTED THIS FILM

Throughout the film Cooked: Survival by Zip Code, filmmaker Judith

Helfand argues that there is an inextricable connection between

environmental injustice and racism as she explores the impact of the

1995 Chicago heat wave that caused hundreds of deaths. The people

most affected, she finds, often live in zip codes that are underserved,

under-resourced, and ill equipped to deal with extreme events like

heat waves, hurricanes, forest fires, and, more recently, pandemics.

An examination of these disasters reveals structural inequalities that

make poor communities and communities of color vulnerable to these

events. The film is an important teaching tool and will promote

critical classroom discussions about how social location, privilege,

and disadvantage intersect to create very different impacts and

experiences within society.

SUGGESTED SUBJECT AREAS

African American Studies Medicine

Environmental Justice Meteorology

Environmental Sciences Political Science

Epidemiology Social Policy

Gerontology Sociology

Management Sciences Urban Economics and Planning

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE FOCUS

The film was inspired by Eric Klinenberg’s book Heat Wave: A Social

Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, which examines the July 1995 heat

wave. Klinenberg and filmmaker Judith Helfand both make the case

for environmental health equity as they point out the damage to

communities inflicted by racially restrictive covenants, redlining by

banks, a lack of safety, exclusion from political engagement in

land-use planning, and inadequate health care, all of which

contribute to a slow-motion environmental and social disaster

created by humans and driven by systemic racism.

SYNOPSIS

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code tells the story of a

tragic heat wave, the most traumatic in U.S. history

at the time, in which 739 citizens died over the

course of a single week, most of them poor, elderly,

and African American.

The film questions existing policy as it explores

a slow-motion disaster that continues to disrupt

and shorten the lives of Chicago residents in

neighborhoods like Englewood, a district ravaged by

pernicious poverty, social isolation, and racism.

This is a place where one resident says, “It’s easier

to buy a gun than a tomato.” One epidemiologist

concludes that 3,200 people die each year from

preventable illnesses in such Chicago

neighborhoods. The filmmaker comes to question

policies that ignore these kinds of ongoing disasters

while preparing, at the same time and at great

expense, for rare events like earthquakes.

The film does find reason to hope for change

because of two community-based initiatives that

address current inequities. Sinai Urban Health

Institute actively reaches out to residents, and an organic farm that

grows vegetables for residents of Englewood calls itself a “human

emergency plan.”

Cooked raises key questions: Can we realign our social priorities?

Can we expand the definition of “disaster” to include socially

patterned deprivation? Would doing so allow us to address the

slow-motion disasters that kill people every day just because they

live in the wrong zip code?

Filmmaker Judith Helfand

KEY LOCATIONS

Westchester County, New York

Englewood, Chicago, Illinois

Cook County, Illinois

New Madrid Seismic Zone, Tennessee

New Orleans, Louisiana

Paducah, Kentucky

PEOPLE FEATURED

Valerie Brown – granddaughter of Alberta Brown,

who died in the heat wave

Richard Daley – mayor of Chicago from 1989 to 2011

Dr. Edmund Donoghue – chief medical examiner, Cook County

Jim DuPont – President, RescUSA, Illinois Urban Search and Rescue

Maureen Finn – forensic scientist,

Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office

Geraldine Flowers – church elder, Sweet Holy Baptist Church

Oreletta Garmon – community health worker

Shirl Gatling – Gatling’s Chapel and Funeral Services

Judith Helfand – film director

Brigadier General John Heltzel – director,

Kentucky Emergency Management

Sadhu Johnston – chief environmental officer, City of Chicago

Eric Klinenberg – author of Heat Wave:

A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago

Michele Landis Dauber – author of The Sympathetic State

Reverend Joseph Ledwell

Mike McReynolds – medical examiner,

Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office

Dr. Linda Rae Murray – medical officer (ret.),

Cook County Department of Public Health

Andy Nebel – reporter at ABC

Toni Preckwinkle – board president,

Cook County Board of Commissioners

Colleen and Jeremiah Scott – residents of Englewood

Celevia Taylor – community health worker,

Sinai Urban Health Institute

Bessie Trotter – Action Coalition of Englewood

Steve Whitman – chief epidemiologist, City of Chicago

Orrin Williams – community organizer, Englewood, Chicago

As the planet heats up,

we are faced with one

natural disaster after

another.

Cooked / Global Environmental Justice Documentaries

WHY I SELECTED THIS FILM

Throughout the film Cooked: Survival by Zip Code, filmmaker Judith

Helfand argues that there is an inextricable connection between

environmental injustice and racism as she explores the impact of the

1995 Chicago heat wave that caused hundreds of deaths. The people

most affected, she finds, often live in zip codes that are underserved,

under-resourced, and ill equipped to deal with extreme events like

heat waves, hurricanes, forest fires, and, more recently, pandemics.

An examination of these disasters reveals structural inequalities that

make poor communities and communities of color vulnerable to these

events. The film is an important teaching tool and will promote

critical classroom discussions about how social location, privilege,

and disadvantage intersect to create very different impacts and

experiences within society.

SUGGESTED SUBJECT AREAS

African American Studies Medicine

Environmental Justice Meteorology

Environmental Sciences Political Science

Epidemiology Social Policy

Gerontology Sociology

Management Sciences Urban Economics and Planning

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE FOCUS

The film was inspired by Eric Klinenberg’s book Heat Wave: A Social

Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, which examines the July 1995 heat

wave. Klinenberg and filmmaker Judith Helfand both make the case

for environmental health equity as they point out the damage to

communities inflicted by racially restrictive covenants, redlining by

banks, a lack of safety, exclusion from political engagement in

land-use planning, and inadequate health care, all of which

contribute to a slow-motion environmental and social disaster

created by humans and driven by systemic racism.

SYNOPSIS

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code tells the story of a

tragic heat wave, the most traumatic in U.S. history

at the time, in which 739 citizens died over the

course of a single week, most of them poor, elderly,

and African American.

The film questions existing policy as it explores

a slow-motion disaster that continues to disrupt

and shorten the lives of Chicago residents in

neighborhoods like Englewood, a district ravaged by

pernicious poverty, social isolation, and racism.

This is a place where one resident says, “It’s easier

to buy a gun than a tomato.” One epidemiologist

concludes that 3,200 people die each year from

preventable illnesses in such Chicago

neighborhoods. The filmmaker comes to question

policies that ignore these kinds of ongoing disasters

while preparing, at the same time and at great

expense, for rare events like earthquakes.

The film does find reason to hope for change

because of two community-based initiatives that

address current inequities. Sinai Urban Health

Institute actively reaches out to residents, and an organic farm that

grows vegetables for residents of Englewood calls itself a “human

emergency plan.”

Cooked raises key questions: Can we realign our social priorities?

Can we expand the definition of “disaster” to include socially

patterned deprivation? Would doing so allow us to address the

slow-motion disasters that kill people every day just because they

live in the wrong zip code?

KEY LOCATIONS

Westchester County, New York

Englewood, Chicago, Illinois

Cook County, Illinois

New Madrid Seismic Zone, Tennessee

New Orleans, Louisiana

Paducah, Kentucky

PEOPLE FEATURED

Valerie Brown – granddaughter of Alberta Brown,

who died in the heat wave

Richard Daley – mayor of Chicago from 1989 to 2011

Dr. Edmund Donoghue – chief medical examiner, Cook County

Jim DuPont – President, RescUSA, Illinois Urban Search and Rescue

Maureen Finn – forensic scientist,

Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office

Geraldine Flowers – church elder, Sweet Holy Baptist Church

Oreletta Garmon – community health worker

Shirl Gatling – Gatling’s Chapel and Funeral Services

Judith Helfand – film director

Brigadier General John Heltzel – director,

Kentucky Emergency Management

Sadhu Johnston – chief environmental officer, City of Chicago

Eric Klinenberg – author of Heat Wave:

A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago

Michele Landis Dauber – author of The Sympathetic State

Reverend Joseph Ledwell

Mike McReynolds – medical examiner,

Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office

Dr. Linda Rae Murray – medical officer (ret.),

Cook County Department of Public Health

Andy Nebel – reporter at ABC

Toni Preckwinkle – board president,

Cook County Board of Commissioners

Colleen and Jeremiah Scott – residents of Englewood

Celevia Taylor – community health worker,

Sinai Urban Health Institute

Bessie Trotter – Action Coalition of Englewood

Steve Whitman – chief epidemiologist, City of Chicago

Orrin Williams – community organizer, Englewood, Chicago

Cooked / Global Environmental Justice Documentaries

VIEWING TIME

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code was originally released as an

82-minute feature-length film and a 54-minute educational version.

The 54-minute version, included in this collection, was broadcast by

PBS on the Independent Lens series.

IF TIME IS SHORT

Where viewing time is limited, five excerpts with a combined length

of 27 minutes could be assigned for viewing or screened in class.

See page 10 for a description of these excerpts.

OUTLINE OF THE 54MINUTE VERSION

Opening: “Disaster through lens of privilege” (00:00–04:09)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand and her family are preparing for Hurricane

Sandy. They are well supplied with generators, flashlights, tools, and

even a boat. She’s confident that her family will be secure and safe as

the storm hits.

Reflecting on her position of privilege in the face of a disaster,

Helfand sets out to explore the story of the catastrophic but largely

forgotten heat wave that killed hundreds of Chicago residents in 1995,

as documented by Eric Klinenberg in Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of

Disaster in Chicago. Retracing that disaster takes Helfand to its

epicenter in South Chicago (opening title).

Non-violent deaths?

(04:10–13:50)

As temperatures rose to 104°F

(40°C) on July 13, 1995, the

residents of Chicago tried to

cope. Mayor Richard Daley

downplayed the danger even

as hospitals were overflowing

with patients suffering from

heat-related illnesses, and

people began to die.

Valerie Brown recalls trying to

reach her grandmother on the

phone. Her grandmother was

found at home, in bed, deceased.

Her windows had been nailed

shut. As the death toll climbed,

refrigerator trucks were brought

in to store bodies.

The Medical Examiner’s Office couldn’t keep up. “It was like a war

zone,” forensic scientist Maureen Finn said. On Saturday morning

there were 87 bodies. The next morning there were 83 more, and then

another 117 the following day.

As the number of deaths mounted the mayor hedged, saying it was

not certain that the deaths were due to excessive heat but allowing

that the number of “non-violent” deaths were increasing. Examining

old footage and exploring the cause of the deaths, Helfand realizes

that people had to make an agonizing choice between staying safe

and staying cool. The death rate is the greatest in poor

neighborhoods on the West and South Sides.

“Everything is about race.” (12:50–17:32)

Medical examiner Mike McReynolds, intake

supervisor at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s

Office, recites a saying that in Chicago,

“Everything is about race.” Helfand asks about the

disproportionate number of deaths among Blacks.

Mayor Daley blames family members of senior

citizens who died all alone and accuses the Medical

Examiner’s Office of exaggerating the number of

deaths. Resident Geraldine Flowers points to a lack

of compassion as a cause. The bodies of 41

unclaimed victims are buried. The death toll rises,

especially in under-served poor neighborhoods.

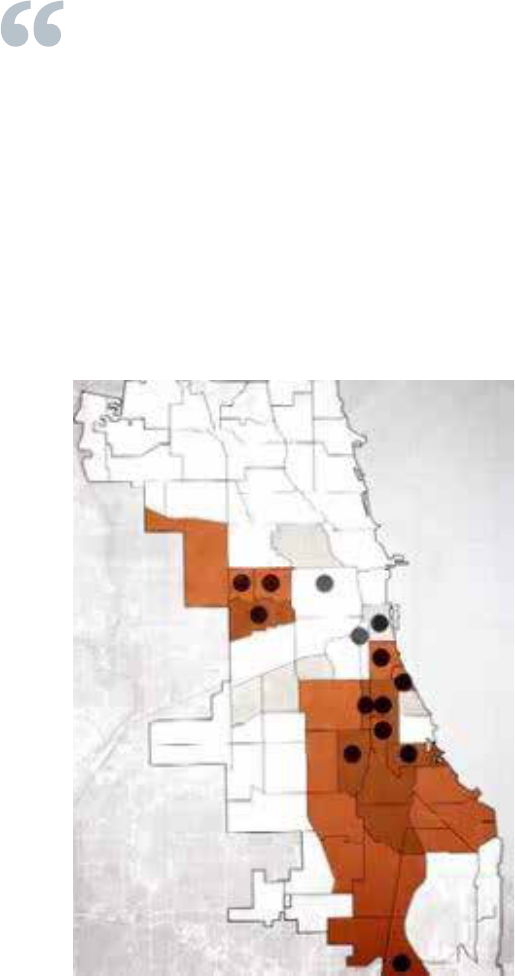

Mapping heat and social conditions

(17:33–21:52)

Steve Whitman, chief epidemiologist for the City of

Chicago, presents a key map showing communities

with high poverty rates, with an overlay showing

where heat-related deaths occurred.

The mayor creates a task force and an emergency

plan, but the plan does not address the issue of

poverty or the social fau

lt lines that leave some

neighborhoods at the mercy of the heat wave.

Whitman says what is needed is “a social evil

remedying plan.”

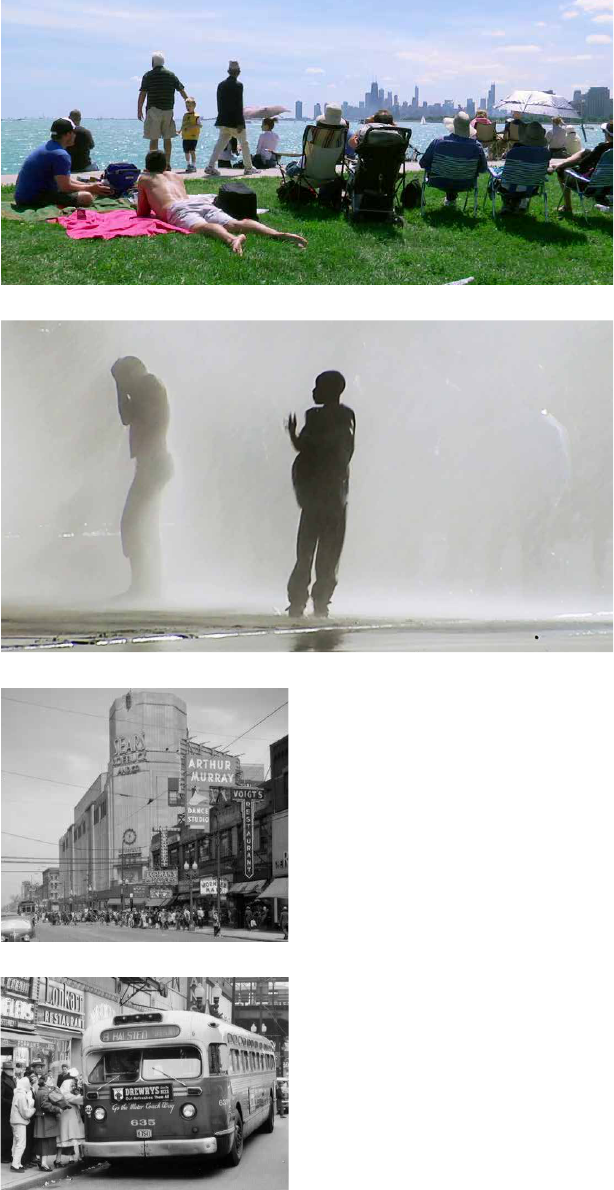

The slow motion disaster

(21:53–24:45)

Police tell children to “back off”

as they shut down the spray

from a hydrant. Meanwhile,

across town by the lakeshore,

the Buckingham Fountain puts

on a spectacular display. Author

Eric Klinenberg worries about

the collective failure to address

these everyday crises, calling

them “disasters in slow motion.”

The aftermath of Hurricane

Katrina in New Orleans provides

further evidence of systemic

denial and neglect.

The discussion pivots to

uncomfortable topics, including

the impact of generations of

racism and denial. The recovery

plan for New Orleans, with its

focus on physical repairs to the

dikes, is an example.

The impact of entrenched racism and denial

(24:46 – 35:45)

In Chicago, the mayor’s climate action plan will develop a “green roof”

for city hall. In South Chicago, community organizer Orrin Williams

laments the continued erosion of a once-vibrant and safe

neighborhood after it was cut off by redlining by the banks.

With gradual disinvestment, he says, communities were

“left out” and “forgotten.”

Chicago epidemiologist Steve Whitman demonstrates that the

differences between Black and white communities in measures of

health are growing. Life expectancy in Black communities is 65 years.

For whites, it is 81 years. Whitman goes on to say that 3,200 people

die in Chicago from health inequities due to racism every year.

If the same number of people died from terrorism, Helfand suggests,

it would be a national tragedy; but dying predictably, from readily

treatable diseases, is not treated as

a disaster.

2. What does Klinenberg mean when he says natural disasters are

more “seen” and visible? Why is it different for unnatural disasters

that are man-made? (04:08–05:15)

3. How does Alberta Washington’s fate resemble those of several

others who perished in the heat wave?

(06:38–07:40, 15:37–16:20)

4. There was a media frenzy related to the heat wave in 1995 in

Chicago. What did the media focus on at the time, and what was

the underreported story? (10:54–11:22)

5. What is problematic in the mayor’s statement that “all neighbor-

hoods were impacted by the heat wave”? What is Klinenberg’s

opinion on that? (19:26–20:21)

6. What was the “heat emergency plan”? Why did epidemiologist

Steve Whitman lack confidence in it? (20:31–21:52)

7. What does Klinenberg mean when he says he is “concerned with

the collective failure to address the everyday crisis, the disaster

in slow motion”? (22:37–23:25)

8. Following the discussion of Hurricane Katrina and its impact on

New Orleans, the focus of the documentary shifts to an examina-

tion of the impact of generations of racism and denial. Why is this

a pivotal moment for the filmmaker and the film? (23:35–24:45)

9. How did the practices of redlining and contract buying exploit

families of color and affect their neighborhoods? (27:41–32:14)

10. Using Steve Whitman’s research findings, how would you describe

a Black neighborhood and the people’s living conditions?

(32:15–35:00) See also Whitman, Steve (2010),

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in Chicago.

11. Note the variety of maps and overlays shown in the film. How do

maps help us examine the health risk factors for African Americans

and their relative vulnerability? Why does the map of heat deaths

overlap with other demographic indicators? Discuss. (32:15–35:00)

12. Disaster preparedness is a well-funded industry. Explain.

(35:10–43:35)

13. What is the difference between a disaster kit and a “get through

the week” kit?

14. How do organizations like Sinai Urban Health Institute and Grow-

ing Home organic farm provide a sign of hope? (45:10–50:05)

15. How would an expanded definition of disaster help in realigning

national priorities? (52:14–53:40)

Disaster-prevention/preparedness (35:45–45:12)

Judith Helfand attends disaster preparedness exercises in Cook County

and in Kentucky, two of many exercises in a rapidly expanding national

industry. Helfand finds expensive resources standing by in preparation

for fire, earthquakes, or floods. Could these resources instead be

applied to communities struck by unnatural disasters? In Kentucky,

the exercise director agrees that emergency management plans don’t

address poverty issues because they are not thought of as disasters.

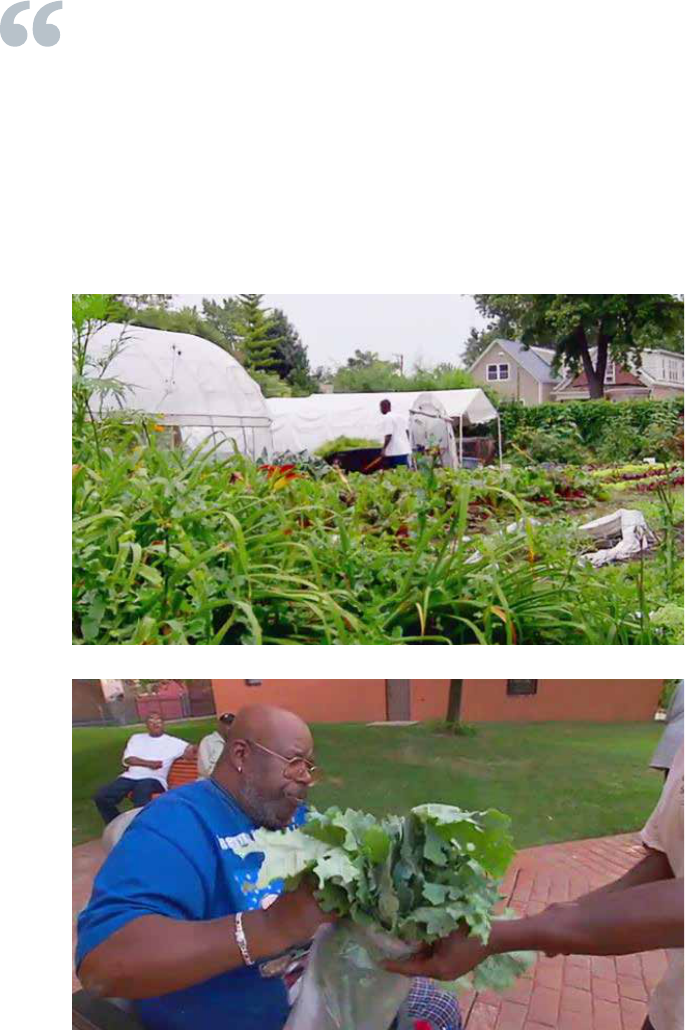

Finding help, and hope, in

communities

(45:13–50:05)

Vulnerable communities rely on

their ingenuity and meager

resources. With help from the

Action Coalition of Englewood,

residents line up to receive a

$150-a-year subsidy on heating

bills. Community health workers

from Sinai Urban Health Institute

reach out to women to alleviate

their health issues. Growing

Home, an organic farm in

Englewood, sees itself as a

“human emergency plan” and a

sign of hope.

Redefining disaster

(50:06-53:40)

The filmmaker calls for

expanding the definition of

disaster so that underlying

conditions that are killing

thousands of people each year

in places like Chicago could be

addressed. Lives could be saved.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

For the 54-minute version

1. Why does Helfand feel privileged as Hurricane Sandy is about to

hit her hometown in Westchester County, New York? How is her

experience of disaster planning different from those of others who

are less fortunate? (00:48–03:33)

WHEN TIME IS SHORTOUTLINE OF EXCERPTS

If time is short, these five selected excerpts, with a total length of

27 minutes, can be viewed in class or assigned for viewing outside of

class. Discussion questions and activities tailored for these excerpts

are suggested below.

An unthinkable disaster: Chicago 1995 (00:00–11:22)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand investigates a catastrophic heat wave that

killed more than 730 people living in under-resourced and under-

served neighborhoods of Chicago in 1995 and uncovers the “unnatural”

causes that caused the deaths of many people, largely elderly and

Black. Many victims were “cooked” to death behind closed doors and

windows. Chicago’s mayor attempted to minimize the crisis, but as

triple-digit temperatures continued, hospitals were inundated.

“It was like a war zone,” a medical examiner recalls.

Environmental injustice: Mapping a slow-motion disaster (15:37–18:10)

Unclaimed victims are buried. The final death tally is 739. Linda Rae

Murray talks about the city’s inappropriate handling of the heat crisis.

Steve Whitman shows a map of Chicago that demonstrates heat

deaths in areas with high poverty rates. Would these people have

died had the heat wave not happened?

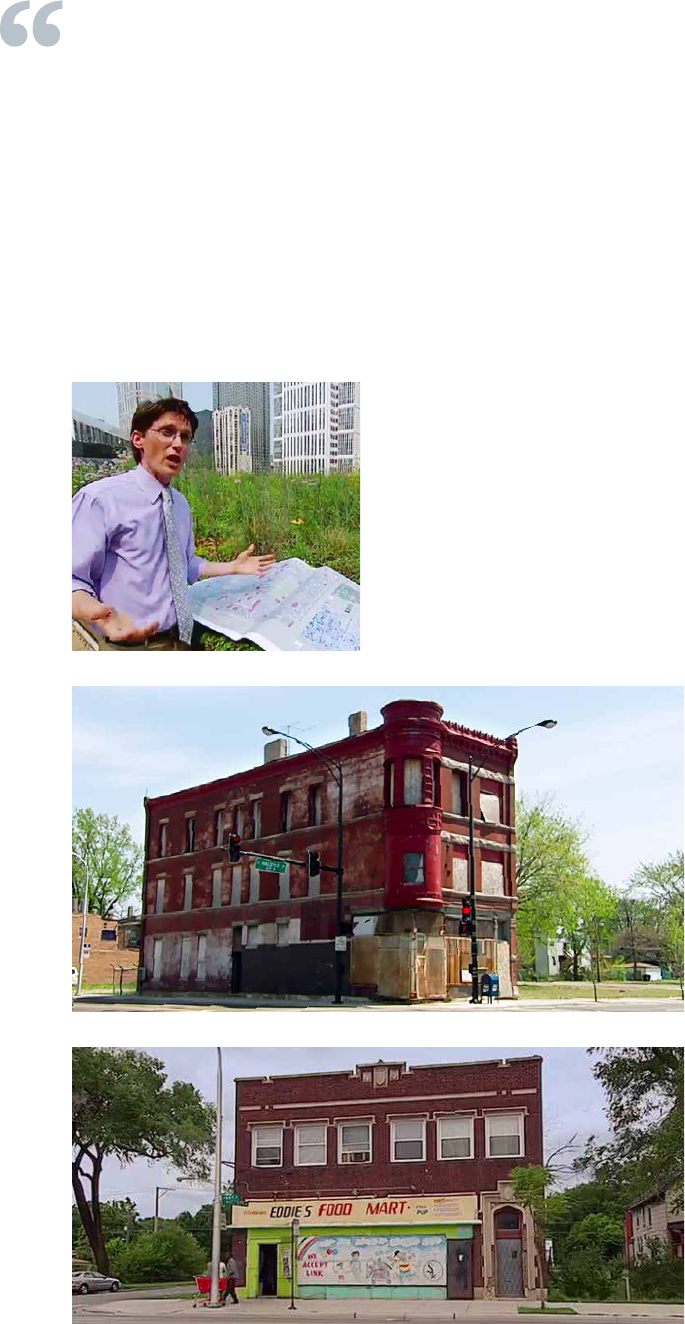

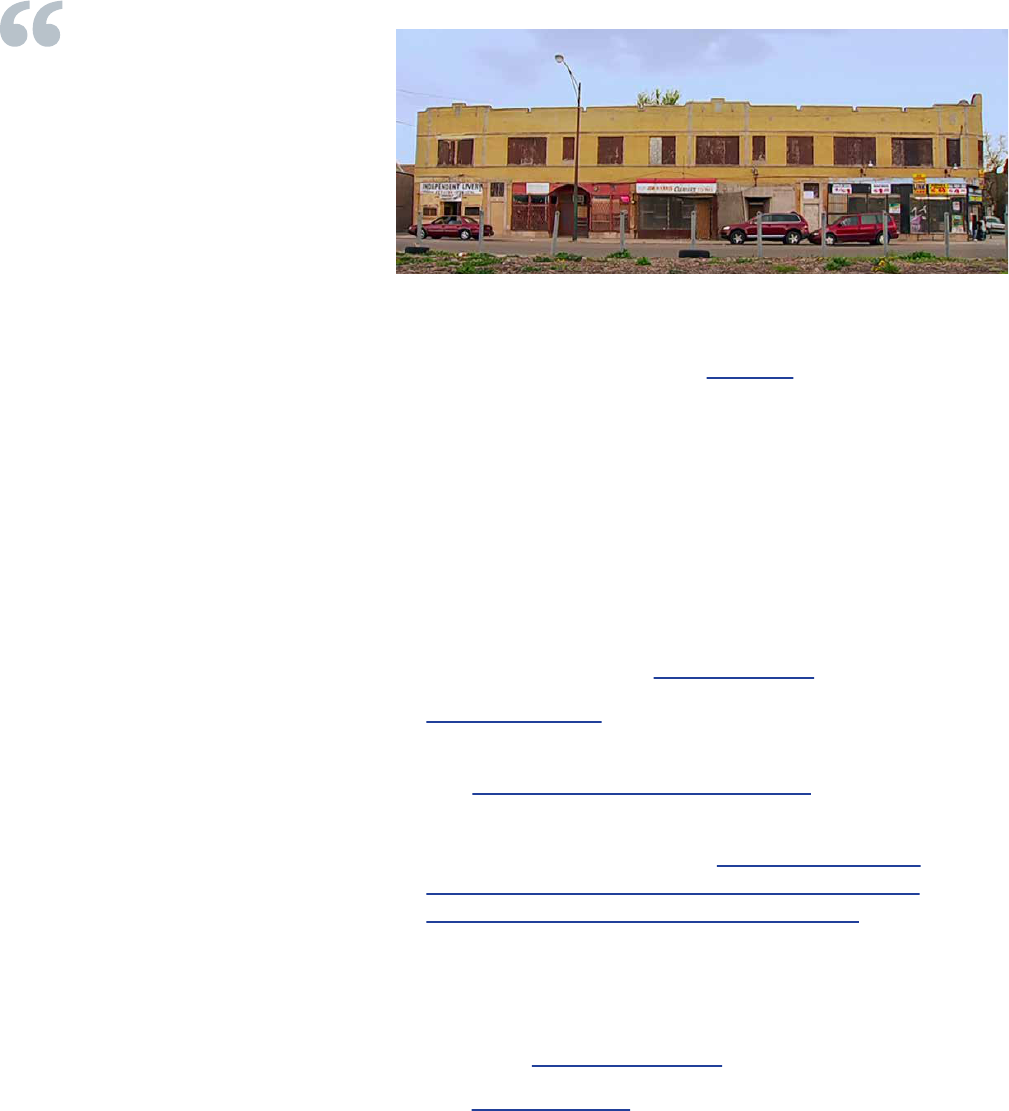

What happened to Orrin

Williams’ neighborhood in

South Chicago? (25:40–29:55)

Community organizer Orrin

Williams takes the filmmaker on

a tour of a once-thriving neigh-

borhood in southwest Chicago.

Englewood has seen redlining

by banks, disinvestment, compa-

nies moving out, churches

burned, boarded-up buildings,

loss of services, and the develop-

ment of a food desert. What was

once a vibrant community

disappeared as redlining and

contract buying deliberately

undermined homeownership by

Black families. These were highly

political decisions, Helfand finds,

that allowed racism to thrive.

Maps reveal the cumulative

impact of generations of denial

and deprivation.

Disaster is big business (35:00–38:18)

Filmmaker Helfand records natural disaster preparedness exercises in

Cook County. On display is $47 million worth of equipment, including

emergency vehicles and a “morgue on wheels;” extra food drills are

practiced and ventilation units readied in case of earthquakes or fires.

Could some of these resources be diverted to communities struck by

unnatural disasters? Or could the definition of disaster be expanded

to include the slow-motion disaster that is consuming neighborhoods

like Englewood?

Signs of hope (45:10–50:05)

Organizations like Action Coalition of Englewood and Growing Home

organic farm are working in the community to address structural

inequities. Helfand finds their work to be of critical importance in

addressing inequities and providing people opportunities for a better

life. By expanding the definition of disaster to include human

emergency, the underlying conditions that are killing thousands

of people each year could be addressed.

ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS TO ACCOMPANY THE

SELECTED EXCERPTS

1. Discuss some of the conditions during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago.

2. What does the film title Cooked mean?

3. Why is the heat wave a forgotten event?

4. What do Steve Whitman’s maps reveal?

5. Are specific neighborhoods more vulnerable to heat waves than

others? Discuss.

6. How have race and

economic class played a role

in Englewood’s decline?

7. What were some of the

processes instituted by

banks and other lenders that

deprived Black residents of

homeownership?

8. Can community action

address the existing social

fault lines? Refer to the

sequence titled

“Signs of hope.”

ACTIVITIES

A. Break into groups and reflect on different identities as well as

diversity within and across groups. Explore assumptions and

expectations from participants identifying with different racial

backgro

unds. Some topics that may be used for this exercise:

– Vic

e President Kamala Harris, a woman and person of color,

achieves political office. How does she describe herself?

How would you describe her?

– Juneteenth was made a federal holiday. Why do some call it the

second Independence Day?

– Commen

t on the CDC’s guidelines to deal with extreme heat

and explore how they impact different communities.

B. W

rite a one-pager about one of the following disasters, discussing

the disproportionate impact on low-income people and

communi-

ties of color as demonstrated by the government’s response:

–

Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley”

–

Flint, Michigan: lead in the water supply

–

The Dakota Access Pipeline and its impact on indigenous

populations

–

Investigate the deadly heat dome in western Canada in 2021.

How many people died and who were the most vulnerable?

How was this disaster similar to or different from the Chicago

heat wave?

– Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony, was damaged by Hurricanes Maria

and Irma in 2017. What was the role of race and racism in

emergency response and recovery in the aftermath of these

hurricanes? Or, more deeply, how did these storms and their

aftermath expose colonial laws and practices resting on white

racial superiority? See Carlos Rodríguez-Diaz and Charlotte

Lewellen-Williams’ Race and Racism as Structural

Determinants for Emergency and Recovery Response in the

Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico.

– Explore your state or provincial emergency response guidelines.

C. COVID-19, also a disaster, is disproportionately impacting environ-

mental justice communities. In your state or province, what steps

have been taken to ensure investments designed to help communi-

ties respond and recover from the pandemic are actually going to

communities that need them the most?

D. COVID-19 in Chicago tells a story of social vulnerability and racial

inequity. Download and discuss this paper.

E. Develop a map of your neighborhood, plotting density, income,

education, housing, health (including COVID-19 levels, if available),

and overall mortality levels.

F. Visit communities that were redlined. Meet with organizations

working in those communities. Develop focus group discussions

and interviews to understand inequity issues.

Read an article on redlining.

G. Explore resource hubs and geographic information system (GIS)

applications that develop racial equity maps.

H. See the catastrophe from the perspective of residents, physicians,

reporters, paramedics, politicians, and relatives of victims.

I. View Chicago’s current heat emergency plan.

J. Discuss whether racial inequities are addressed in FEMA’s

National Disaster Recovery Plan: Chicago Tribune Article

Highlights Significant Disparities in FEMA Disaster Relief

Response Between White and Black Communities.

K. Find out about environmental justice communities in and

around where you live. Map them according to location, health,

education, and income indices.

L. Read about environmental racism.

M.

View a panel discussion that includes filmmaker Judith Helfand and

Cook County Board of Commissioners President Toni Preckwinkle.

Cooked / Global Environmental Justice Documentaries

VIEWING TIME

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code was originally released as an

82-minute feature-length film and a 54-minute educational version.

The 54-minute version, included in this collection, was broadcast by

PBS on the Independent Lens series.

IF TIME IS SHORT

Where viewing time is limited, five excerpts with a combined length

of 27 minutes could be assigned for viewing or screened in class.

See page 10 for a description of these excerpts.

OUTLINE OF THE 54MINUTE VERSION

Opening: “Disaster through lens of privilege” (00:00–04:09)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand and her family are preparing for Hurricane

Sandy. They are well supplied with generators, flashlights, tools, and

even a boat. She’s confident that her family will be secure and safe as

the storm hits.

Reflecting on her position of privilege in the face of a disaster,

Helfand sets out to explore the story of the catastrophic but largely

forgotten heat wave that killed hundreds of Chicago residents in 1995,

as documented by Eric Klinenberg in Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of

Disaster in Chicago. Retracing that disaster takes Helfand to its

epicenter in South Chicago (opening title).

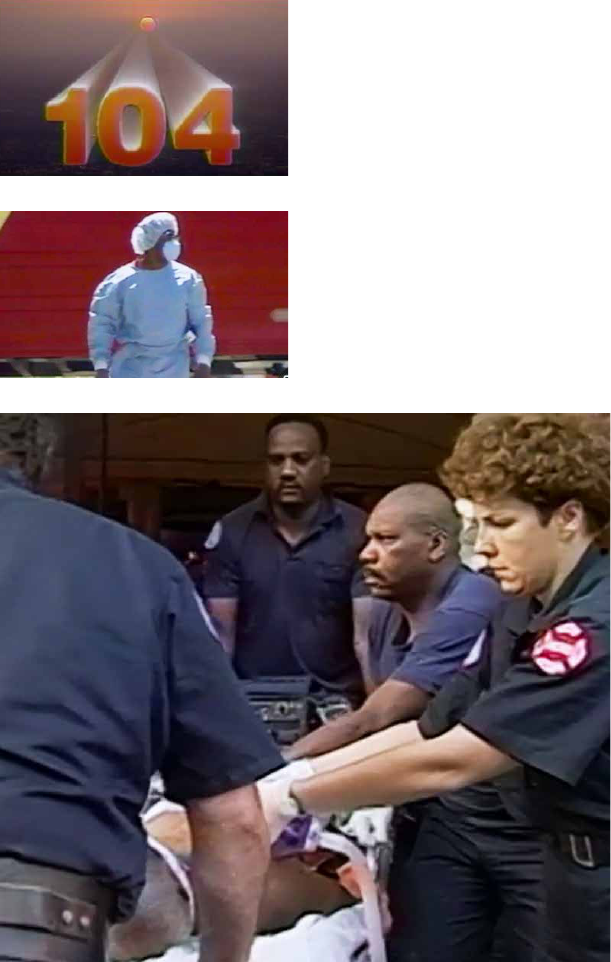

Non-violent deaths?

(04:10–13:50)

As temperatures rose to 104°F

(40°C) on July 13, 1995, the

residents of Chicago tried to

cope. Mayor Richard Daley

downplayed the danger even

as hospitals were overflowing

with patients suffering from

heat-related illnesses, and

people began to die.

Valerie Brown recalls trying to

reach her grandmother on the

phone. Her grandmother was

found at home, in bed, deceased.

Her windows had been nailed

shut. As the death toll climbed,

refrigerator trucks were brought

in to store bodies.

The Medical Examiner’s Office couldn’t keep up. “It was like a war

zone,” forensic scientist Maureen Finn said. On Saturday morning

there were 87 bodies. The next morning there were 83 more, and then

another 117 the following day.

As the number of deaths mounted the mayor hedged, saying it was

not certain that the deaths were due to excessive heat but allowing

that the number of “non-violent” deaths were increasing. Examining

old footage and exploring the cause of the deaths, Helfand realizes

that people had to make an agonizing choice between staying safe

and staying cool. The death rate is the greatest in poor

neighborhoods on the West and South Sides.

“Everything is about race.” (12:50–17:32)

Medical examiner Mike McReynolds, intake

supervisor at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s

Office, recites a saying that in Chicago,

“Everything is about race.” Helfand asks about the

disproportionate number of deaths among Blacks.

Mayor Daley blames family members of senior

citizens who died all alone and accuses the Medical

Examiner’s Office of exaggerating the number of

deaths. Resident Geraldine Flowers points to a lack

of compassion as a cause. The bodies of 41

unclaimed victims are buried. The death toll rises,

especially in under-served poor neighborhoods.

Mapping heat and social conditions

(17:33–21:52)

Steve Whitman, chief epidemiologist for the City of

Chicago, presents a key map showing communities

with high poverty rates, with an overlay showing

where heat-related deaths occurred.

The mayor creates a task force and an emergency

plan, but the plan does not address the issue of

poverty or the social fau

lt lines that leave some

neighborhoods at the mercy of the heat wave.

Whitman says what is needed is “a social evil

remedying plan.”

The slow motion disaster

(21:53–24:45)

Police tell children to “back off”

as they shut down the spray

from a hydrant. Meanwhile,

across town by the lakeshore,

the Buckingham Fountain puts

on a spectacular display. Author

Eric Klinenberg worries about

the collective failure to address

these everyday crises, calling

them “disasters in slow motion.”

The aftermath of Hurricane

Katrina in New Orleans provides

further evidence of systemic

denial and neglect.

The discussion pivots to

uncomfortable topics, including

the impact of generations of

racism and denial. The recovery

plan for New Orleans, with its

focus on physical repairs to the

dikes, is an example.

The impact of entrenched racism and denial

(24:46 – 35:45)

In Chicago, the mayor’s climate action plan will develop a “green roof”

for city hall. In South Chicago, community organizer Orrin Williams

laments the continued erosion of a once-vibrant and safe

neighborhood after it was cut off by redlining by the banks.

With gradual disinvestment, he says, communities were

“left out” and “forgotten.”

Chicago epidemiologist Steve Whitman demonstrates that the

differences between Black and white communities in measures of

health are growing. Life expectancy in Black communities is 65 years.

For whites, it is 81 years. Whitman goes on to say that 3,200 people

die in Chicago from health inequities due to racism every year.

If the same number of people died from terrorism, Helfand suggests,

it would be a national tragedy; but dying predictably, from readily

treatable diseases, is not treated as

a disaster.

2. What does Klinenberg mean when he says natural disasters are

more “seen” and visible? Why is it different for unnatural disasters

that are man-made? (04:08–05:15)

3. How does Alberta Washington’s fate resemble those of several

others who perished in the heat wave?

(06:38–07:40, 15:37–16:20)

4. There was a media frenzy related to the heat wave in 1995 in

Chicago. What did the media focus on at the time, and what was

the underreported story? (10:54–11:22)

5. What is problematic in the mayor’s statement that “all neighbor-

hoods were impacted by the heat wave”? What is Klinenberg’s

opinion on that? (19:26–20:21)

6. What was the “heat emergency plan”? Why did epidemiologist

Steve Whitman lack confidence in it? (20:31–21:52)

7. What does Klinenberg mean when he says he is “concerned with

the collective failure to address the everyday crisis, the disaster

in slow motion”? (22:37–23:25)

8. Following the discussion of Hurricane Katrina and its impact on

New Orleans, the focus of the documentary shifts to an examina-

tion of the impact of generations of racism and denial. Why is this

a pivotal moment for the filmmaker and the film? (23:35–24:45)

9. How did the practices of redlining and contract buying exploit

families of color and affect their neighborhoods? (27:41–32:14)

10. Using Steve Whitman’s research findings, how would you describe

a Black neighborhood and the people’s living conditions?

(32:15–35:00) See also Whitman, Steve (2010),

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in Chicago.

11. Note the variety of maps and overlays shown in the film. How do

maps help us examine the health risk factors for African Americans

and their relative vulnerability? Why does the map of heat deaths

overlap with other demographic indicators? Discuss. (32:15–35:00)

12. Disaster preparedness is a well-funded industry. Explain.

(35:10–43:35)

13. What is the difference between a disaster kit and a “get through

the week” kit?

14. How do organizations like Sinai Urban Health Institute and Grow-

ing Home organic farm provide a sign of hope? (45:10–50:05)

15. How would an expanded definition of disaster help in realigning

national priorities? (52:14–53:40)

Disaster-prevention/preparedness (35:45–45:12)

Judith Helfand attends disaster preparedness exercises in Cook County

and in Kentucky, two of many exercises in a rapidly expanding national

industry. Helfand finds expensive resources standing by in preparation

for fire, earthquakes, or floods. Could these resources instead be

applied to communities struck by unnatural disasters? In Kentucky,

the exercise director agrees that emergency management plans don’t

address poverty issues because they are not thought of as disasters.

Finding help, and hope, in

communities

(45:13–50:05)

Vulnerable communities rely on

their ingenuity and meager

resources. With help from the

Action Coalition of Englewood,

residents line up to receive a

$150-a-year subsidy on heating

bills. Community health workers

from Sinai Urban Health Institute

reach out to women to alleviate

their health issues. Growing

Home, an organic farm in

Englewood, sees itself as a

“human emergency plan” and a

sign of hope.

Redefining disaster

(50:06-53:40)

The filmmaker calls for

expanding the definition of

disaster so that underlying

conditions that are killing

thousands of people each year

in places like Chicago could be

addressed. Lives could be saved.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

For the 54-minute version

1. Why does Helfand feel privileged as Hurricane Sandy is about to

hit her hometown in Westchester County, New York? How is her

experience of disaster planning different from those of others who

are less fortunate? (00:48–03:33)

WHEN TIME IS SHORTOUTLINE OF EXCERPTS

If time is short, these five selected excerpts, with a total length of

27 minutes, can be viewed in class or assigned for viewing outside of

class. Discussion questions and activities tailored for these excerpts

are suggested below.

An unthinkable disaster: Chicago 1995 (00:00–11:22)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand investigates a catastrophic heat wave that

killed more than 730 people living in under-resourced and under-

served neighborhoods of Chicago in 1995 and uncovers the “unnatural”

causes that caused the deaths of many people, largely elderly and

Black. Many victims were “cooked” to death behind closed doors and

windows. Chicago’s mayor attempted to minimize the crisis, but as

triple-digit temperatures continued, hospitals were inundated.

“It was like a war zone,” a medical examiner recalls.

Environmental injustice: Mapping a slow-motion disaster (15:37–18:10)

Unclaimed victims are buried. The final death tally is 739. Linda Rae

Murray talks about the city’s inappropriate handling of the heat crisis.

Steve Whitman shows a map of Chicago that demonstrates heat

deaths in areas with high poverty rates. Would these people have

died had the heat wave not happened?

What happened to Orrin

Williams’ neighborhood in

South Chicago? (25:40–29:55)

Community organizer Orrin

Williams takes the filmmaker on

a tour of a once-thriving neigh-

borhood in southwest Chicago.

Englewood has seen redlining

by banks, disinvestment, compa-

nies moving out, churches

burned, boarded-up buildings,

loss of services, and the develop-

ment of a food desert. What was

once a vibrant community

disappeared as redlining and

contract buying deliberately

undermined homeownership by

Black families. These were highly

political decisions, Helfand finds,

that allowed racism to thrive.

Maps reveal the cumulative

impact of generations of denial

and deprivation.

Disaster is big business (35:00–38:18)

Filmmaker Helfand records natural disaster preparedness exercises in

Cook County. On display is $47 million worth of equipment, including

emergency vehicles and a “morgue on wheels;” extra food drills are

practiced and ventilation units readied in case of earthquakes or fires.

Could some of these resources be diverted to communities struck by

unnatural disasters? Or could the definition of disaster be expanded

to include the slow-motion disaster that is consuming neighborhoods

like Englewood?

Signs of hope (45:10–50:05)

Organizations like Action Coalition of Englewood and Growing Home

organic farm are working in the community to address structural

inequities. Helfand finds their work to be of critical importance in

addressing inequities and providing people opportunities for a better

life. By expanding the definition of disaster to include human

emergency, the underlying conditions that are killing thousands

of people each year could be addressed.

ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS TO ACCOMPANY THE

SELECTED EXCERPTS

1. Discuss some of the conditions during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago.

2. What does the film title Cooked mean?

3. Why is the heat wave a forgotten event?

4. What do Steve Whitman’s maps reveal?

5. Are specific neighborhoods more vulnerable to heat waves than

others? Discuss.

6. How have race and

economic class played a role

in Englewood’s decline?

7. What were some of the

processes instituted by

banks and other lenders that

deprived Black residents of

homeownership?

8. Can community action

address the existing social

fault lines? Refer to the

sequence titled

“Signs of hope.”

ACTIVITIES

A. Break into groups and reflect on different identities as well as

diversity within and across groups. Explore assumptions and

expectations from participants identifying with different racial

backgro

unds. Some topics that may be used for this exercise:

– Vic

e President Kamala Harris, a woman and person of color,

achieves political office. How does she describe herself?

How would you describe her?

– Juneteenth was made a federal holiday. Why do some call it the

second Independence Day?

– Commen

t on the CDC’s guidelines to deal with extreme heat

and explore how they impact different communities.

B. W

rite a one-pager about one of the following disasters, discussing

the disproportionate impact on low-income people and

communi-

ties of color as demonstrated by the government’s response:

–

Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley”

–

Flint, Michigan: lead in the water supply

–

The Dakota Access Pipeline and its impact on indigenous

populations

–

Investigate the deadly heat dome in western Canada in 2021.

How many people died and who were the most vulnerable?

How was this disaster similar to or different from the Chicago

heat wave?

– Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony, was damaged by Hurricanes Maria

and Irma in 2017. What was the role of race and racism in

emergency response and recovery in the aftermath of these

hurricanes? Or, more deeply, how did these storms and their

aftermath expose colonial laws and practices resting on white

racial superiority? See Carlos Rodríguez-Diaz and Charlotte

Lewellen-Williams’ Race and Racism as Structural

Determinants for Emergency and Recovery Response in the

Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico.

– Explore your state or provincial emergency response guidelines.

C. COVID-19, also a disaster, is disproportionately impacting environ-

mental justice communities. In your state or province, what steps

have been taken to ensure investments designed to help communi-

ties respond and recover from the pandemic are actually going to

communities that need them the most?

The health inequities

that exist are not

accidents. They are

created by people.

Linda Rae Murray,

medical officer, Cook County

D. COVID-19 in Chicago tells a story of social vulnerability and racial

inequity. Download and discuss this paper.

E. Develop a map of your neighborhood, plotting density, income,

education, housing, health (including COVID-19 levels, if available),

and overall mortality levels.

F. Visit communities that were redlined. Meet with organizations

working in those communities. Develop focus group discussions

and interviews to understand inequity issues.

Read an article on redlining.

G. Explore resource hubs and geographic information system (GIS)

applications that develop racial equity maps.

H. See the catastrophe from the perspective of residents, physicians,

reporters, paramedics, politicians, and relatives of victims.

I. View Chicago’s current heat emergency plan.

J. Discuss whether racial inequities are addressed in FEMA’s

National Disaster Recovery Plan: Chicago Tribune Article

Highlights Significant Disparities in FEMA Disaster Relief

Response Between White and Black Communities.

K. Find out about environmental justice communities in and

around where you live. Map them according to location, health,

education, and income indices.

L. Read about environmental racism.

M.

View a panel discussion that includes filmmaker Judith Helfand and

Cook County Board of Commissioners President Toni Preckwinkle.

Cooked / Global Environmental Justice Documentaries

VIEWING TIME

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code was originally released as an

82-minute feature-length film and a 54-minute educational version.

The 54-minute version, included in this collection, was broadcast by

PBS on the Independent Lens series.

IF TIME IS SHORT

Where viewing time is limited, five excerpts with a combined length

of 27 minutes could be assigned for viewing or screened in class.

See page 10 for a description of these excerpts.

OUTLINE OF THE 54MINUTE VERSION

Opening: “Disaster through lens of privilege” (00:00–04:09)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand and her family are preparing for Hurricane

Sandy. They are well supplied with generators, flashlights, tools, and

even a boat. She’s confident that her family will be secure and safe as

the storm hits.

Reflecting on her position of privilege in the face of a disaster,

Helfand sets out to explore the story of the catastrophic but largely

forgotten heat wave that killed hundreds of Chicago residents in 1995,

as documented by Eric Klinenberg in Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of

Disaster in Chicago. Retracing that disaster takes Helfand to its

epicenter in South Chicago (opening title).

Non-violent deaths?

(04:10–13:50)

As temperatures rose to 104°F

(40°C) on July 13, 1995, the

residents of Chicago tried to

cope. Mayor Richard Daley

downplayed the danger even

as hospitals were overflowing

with patients suffering from

heat-related illnesses, and

people began to die.

Valerie Brown recalls trying to

reach her grandmother on the

phone. Her grandmother was

found at home, in bed, deceased.

Her windows had been nailed

shut. As the death toll climbed,

refrigerator trucks were brought

in to store bodies.

The Medical Examiner’s Office couldn’t keep up. “It was like a war

zone,” forensic scientist Maureen Finn said. On Saturday morning

there were 87 bodies. The next morning there were 83 more, and then

another 117 the following day.

As the number of deaths mounted the mayor hedged, saying it was

not certain that the deaths were due to excessive heat but allowing

that the number of “non-violent” deaths were increasing. Examining

old footage and exploring the cause of the deaths, Helfand realizes

that people had to make an agonizing choice between staying safe

and staying cool. The death rate is the greatest in poor

neighborhoods on the West and South Sides.

“Everything is about race.” (12:50–17:32)

Medical examiner Mike McReynolds, intake

supervisor at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s

Office, recites a saying that in Chicago,

“Everything is about race.” Helfand asks about the

disproportionate number of deaths among Blacks.

Mayor Daley blames family members of senior

citizens who died all alone and accuses the Medical

Examiner’s Office of exaggerating the number of

deaths. Resident Geraldine Flowers points to a lack

of compassion as a cause. The bodies of 41

unclaimed victims are buried. The death toll rises,

especially in under-served poor neighborhoods.

Mapping heat and social conditions

(17:33–21:52)

Steve Whitman, chief epidemiologist for the City of

Chicago, presents a key map showing communities

with high poverty rates, with an overlay showing

where heat-related deaths occurred.

The mayor creates a task force and an emergency

plan, but the plan does not address the issue of

poverty or the social fau

lt lines that leave some

neighborhoods at the mercy of the heat wave.

Whitman says what is needed is “a social evil

remedying plan.”

The slow motion disaster

(21:53–24:45)

Police tell children to “back off”

as they shut down the spray

from a hydrant. Meanwhile,

across town by the lakeshore,

the Buckingham Fountain puts

on a spectacular display. Author

Eric Klinenberg worries about

the collective failure to address

these everyday crises, calling

them “disasters in slow motion.”

The aftermath of Hurricane

Katrina in New Orleans provides

further evidence of systemic

denial and neglect.

The discussion pivots to

uncomfortable topics, including

the impact of generations of

racism and denial. The recovery

plan for New Orleans, with its

focus on physical repairs to the

dikes, is an example.

The impact of entrenched racism and denial

(24:46 – 35:45)

In Chicago, the mayor’s climate action plan will develop a “green roof”

for city hall. In South Chicago, community organizer Orrin Williams

laments the continued erosion of a once-vibrant and safe

neighborhood after it was cut off by redlining by the banks.

With gradual disinvestment, he says, communities were

“left out” and “forgotten.”

Chicago epidemiologist Steve Whitman demonstrates that the

differences between Black and white communities in measures of

health are growing. Life expectancy in Black communities is 65 years.

For whites, it is 81 years. Whitman goes on to say that 3,200 people

die in Chicago from health inequities due to racism every year.

If the same number of people died from terrorism, Helfand suggests,

it would be a national tragedy; but dying predictably, from readily

treatable diseases, is not treated as

a disaster.

2. What does Klinenberg mean when he says natural disasters are

more “seen” and visible? Why is it different for unnatural disasters

that are man-made? (04:08–05:15)

3. How does Alberta Washington’s fate resemble those of several

others who perished in the heat wave?

(06:38–07:40, 15:37–16:20)

4. There was a media frenzy related to the heat wave in 1995 in

Chicago. What did the media focus on at the time, and what was

the underreported story? (10:54–11:22)

5. What is problematic in the mayor’s statement that “all neighbor-

hoods were impacted by the heat wave”? What is Klinenberg’s

opinion on that? (19:26–20:21)

6. What was the “heat emergency plan”? Why did epidemiologist

Steve Whitman lack confidence in it? (20:31–21:52)

7. What does Klinenberg mean when he says he is “concerned with

the collective failure to address the everyday crisis, the disaster

in slow motion”? (22:37–23:25)

8. Following the discussion of Hurricane Katrina and its impact on

New Orleans, the focus of the documentary shifts to an examina-

tion of the impact of generations of racism and denial. Why is this

a pivotal moment for the filmmaker and the film? (23:35–24:45)

9. How did the practices of redlining and contract buying exploit

families of color and affect their neighborhoods? (27:41–32:14)

10. Using Steve Whitman’s research findings, how would you describe

a Black neighborhood and the people’s living conditions?

(32:15–35:00) See also Whitman, Steve (2010),

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in Chicago.

11. Note the variety of maps and overlays shown in the film. How do

maps help us examine the health risk factors for African Americans

and their relative vulnerability? Why does the map of heat deaths

overlap with other demographic indicators? Discuss. (32:15–35:00)

12. Disaster preparedness is a well-funded industry. Explain.

(35:10–43:35)

13. What is the difference between a disaster kit and a “get through

the week” kit?

14. How do organizations like Sinai Urban Health Institute and Grow-

ing Home organic farm provide a sign of hope? (45:10–50:05)

15. How would an expanded definition of disaster help in realigning

national priorities? (52:14–53:40)

Disaster-prevention/preparedness (35:45–45:12)

Judith Helfand attends disaster preparedness exercises in Cook County

and in Kentucky, two of many exercises in a rapidly expanding national

industry. Helfand finds expensive resources standing by in preparation

for fire, earthquakes, or floods. Could these resources instead be

applied to communities struck by unnatural disasters? In Kentucky,

the exercise director agrees that emergency management plans don’t

address poverty issues because they are not thought of as disasters.

Finding help, and hope, in

communities

(45:13–50:05)

Vulnerable communities rely on

their ingenuity and meager

resources. With help from the

Action Coalition of Englewood,

residents line up to receive a

$150-a-year subsidy on heating

bills. Community health workers

from Sinai Urban Health Institute

reach out to women to alleviate

their health issues. Growing

Home, an organic farm in

Englewood, sees itself as a

“human emergency plan” and a

sign of hope.

Redefining disaster

(50:06-53:40)

The filmmaker calls for

expanding the definition of

disaster so that underlying

conditions that are killing

thousands of people each year

in places like Chicago could be

addressed. Lives could be saved.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

For the 54-minute version

1. Why does Helfand feel privileged as Hurricane Sandy is about to

hit her hometown in Westchester County, New York? How is her

experience of disaster planning different from those of others who

are less fortunate? (00:48–03:33)

WHEN TIME IS SHORTOUTLINE OF EXCERPTS

If time is short, these five selected excerpts, with a total length of

27 minutes, can be viewed in class or assigned for viewing outside of

class. Discussion questions and activities tailored for these excerpts

are suggested below.

An unthinkable disaster: Chicago 1995 (00:00–11:22)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand investigates a catastrophic heat wave that

killed more than 730 people living in under-resourced and under-

served neighborhoods of Chicago in 1995 and uncovers the “unnatural”

causes that caused the deaths of many people, largely elderly and

Black. Many victims were “cooked” to death behind closed doors and

windows. Chicago’s mayor attempted to minimize the crisis, but as

triple-digit temperatures continued, hospitals were inundated.

“It was like a war zone,” a medical examiner recalls.

Environmental injustice: Mapping a slow-motion disaster (15:37–18:10)

Unclaimed victims are buried. The final death tally is 739. Linda Rae

Murray talks about the city’s inappropriate handling of the heat crisis.

Steve Whitman shows a map of Chicago that demonstrates heat

deaths in areas with high poverty rates. Would these people have

died had the heat wave not happened?

What happened to Orrin

Williams’ neighborhood in

South Chicago? (25:40–29:55)

Community organizer Orrin

Williams takes the filmmaker on

a tour of a once-thriving neigh-

borhood in southwest Chicago.

Englewood has seen redlining

by banks, disinvestment, compa-

nies moving out, churches

burned, boarded-up buildings,

loss of services, and the develop-

ment of a food desert. What was

once a vibrant community

disappeared as redlining and

contract buying deliberately

undermined homeownership by

Black families. These were highly

political decisions, Helfand finds,

that allowed racism to thrive.

Maps reveal the cumulative

impact of generations of denial

and deprivation.

Disaster is big business (35:00–38:18)

Filmmaker Helfand records natural disaster preparedness exercises in

Cook County. On display is $47 million worth of equipment, including

emergency vehicles and a “morgue on wheels;” extra food drills are

practiced and ventilation units readied in case of earthquakes or fires.

Could some of these resources be diverted to communities struck by

unnatural disasters? Or could the definition of disaster be expanded

to include the slow-motion disaster that is consuming neighborhoods

like Englewood?

Signs of hope (45:10–50:05)

Organizations like Action Coalition of Englewood and Growing Home

organic farm are working in the community to address structural

inequities. Helfand finds their work to be of critical importance in

addressing inequities and providing people opportunities for a better

life. By expanding the definition of disaster to include human

emergency, the underlying conditions that are killing thousands

of people each year could be addressed.

ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS TO ACCOMPANY THE

SELECTED EXCERPTS

1. Discuss some of the conditions during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago.

2. What does the film title Cooked mean?

3. Why is the heat wave a forgotten event?

4. What do Steve Whitman’s maps reveal?

5. Are specific neighborhoods more vulnerable to heat waves than

others? Discuss.

6. How have race and

economic class played a role

in Englewood’s decline?

7. What were some of the

processes instituted by

banks and other lenders that

deprived Black residents of

homeownership?

8. Can community action

address the existing social

fault lines? Refer to the

sequence titled

“Signs of hope.”

ACTIVITIES

A. Break into groups and reflect on different identities as well as

diversity within and across groups. Explore assumptions and

expectations from participants identifying with different racial

backgro

unds. Some topics that may be used for this exercise:

– Vic

e President Kamala Harris, a woman and person of color,

achieves political office. How does she describe herself?

How would you describe her?

– Juneteenth was made a federal holiday. Why do some call it the

second Independence Day?

– Commen

t on the CDC’s guidelines to deal with extreme heat

and explore how they impact different communities.

B. W

rite a one-pager about one of the following disasters, discussing

the disproportionate impact on low-income people and

communi-

ties of color as demonstrated by the government’s response:

–

Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley”

–

Flint, Michigan: lead in the water supply

–

The Dakota Access Pipeline and its impact on indigenous

populations

–

Investigate the deadly heat dome in western Canada in 2021.

How many people died and who were the most vulnerable?

How was this disaster similar to or different from the Chicago

heat wave?

– Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony, was damaged by Hurricanes Maria

and Irma in 2017. What was the role of race and racism in

emergency response and recovery in the aftermath of these

hurricanes? Or, more deeply, how did these storms and their

aftermath expose colonial laws and practices resting on white

racial superiority? See Carlos Rodríguez-Diaz and Charlotte

Lewellen-Williams’ Race and Racism as Structural

Determinants for Emergency and Recovery Response in the

Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico.

– Explore your state or provincial emergency response guidelines.

C. COVID-19, also a disaster, is disproportionately impacting environ-

mental justice communities. In your state or province, what steps

have been taken to ensure investments designed to help communi-

ties respond and recover from the pandemic are actually going to

communities that need them the most?

D. COVID-19 in Chicago tells a story of social vulnerability and racial

inequity. Download and discuss this paper.

E. Develop a map of your neighborhood, plotting density, income,

education, housing, health (including COVID-19 levels, if available),

and overall mortality levels.

F. Visit communities that were redlined. Meet with organizations

working in those communities. Develop focus group discussions

and interviews to understand inequity issues.

Read an article on redlining.

G. Explore resource hubs and geographic information system (GIS)

applications that develop racial equity maps.

H. See the catastrophe from the perspective of residents, physicians,

reporters, paramedics, politicians, and relatives of victims.

I. View Chicago’s current heat emergency plan.

J. Discuss whether racial inequities are addressed in FEMA’s

National Disaster Recovery Plan: Chicago Tribune Article

Highlights Significant Disparities in FEMA Disaster Relief

Response Between White and Black Communities.

K. Find out about environmental justice communities in and

around where you live. Map them according to location, health,

education, and income indices.

L. Read about environmental racism.

M.

View a panel discussion that includes filmmaker Judith Helfand and

Cook County Board of Commissioners President Toni Preckwinkle.

Cooked / Global Environmental Justice Documentaries

VIEWING TIME

Cooked: Survival by Zip Code was originally released as an

82-minute feature-length film and a 54-minute educational version.

The 54-minute version, included in this collection, was broadcast by

PBS on the Independent Lens series.

IF TIME IS SHORT

Where viewing time is limited, five excerpts with a combined length

of 27 minutes could be assigned for viewing or screened in class.

See page 10 for a description of these excerpts.

OUTLINE OF THE 54MINUTE VERSION

Opening: “Disaster through lens of privilege” (00:00–04:09)

Filmmaker Judith Helfand and her family are preparing for Hurricane

Sandy. They are well supplied with generators, flashlights, tools, and

even a boat. She’s confident that her family will be secure and safe as

the storm hits.

Reflecting on her position of privilege in the face of a disaster,

Helfand sets out to explore the story of the catastrophic but largely

forgotten heat wave that killed hundreds of Chicago residents in 1995,

as documented by Eric Klinenberg in Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of

Disaster in Chicago. Retracing that disaster takes Helfand to its

epicenter in South Chicago (opening title).

Non-violent deaths?

(04:10–13:50)

As temperatures rose to 104°F

(40°C) on July 13, 1995, the

residents of Chicago tried to

cope. Mayor Richard Daley

downplayed the danger even

as hospitals were overflowing

with patients suffering from

heat-related illnesses, and

people began to die.

Valerie Brown recalls trying to

reach her grandmother on the

phone. Her grandmother was

found at home, in bed, deceased.

Her windows had been nailed

shut. As the death toll climbed,

refrigerator trucks were brought

in to store bodies.

The Medical Examiner’s Office couldn’t keep up. “It was like a war

zone,” forensic scientist Maureen Finn said. On Saturday morning

there were 87 bodies. The next morning there were 83 more, and then

another 117 the following day.

As the number of deaths mounted the mayor hedged, saying it was

not certain that the deaths were due to excessive heat but allowing

that the number of “non-violent” deaths were increasing. Examining

old footage and exploring the cause of the deaths, Helfand realizes

that people had to make an agonizing choice between staying safe

and staying cool. The death rate is the greatest in poor

neighborhoods on the West and South Sides.

“Everything is about race.” (12:50–17:32)

Medical examiner Mike McReynolds, intake

supervisor at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s

Office, recites a saying that in Chicago,

“Everything is about race.” Helfand asks about the

disproportionate number of deaths among Blacks.

Mayor Daley blames family members of senior

citizens who died all alone and accuses the Medical

Examiner’s Office of exaggerating the number of

deaths. Resident Geraldine Flowers points to a lack

of compassion as a cause. The bodies of 41

unclaimed victims are buried. The death toll rises,

especially in under-served poor neighborhoods.

Mapping heat and social conditions

(17:33–21:52)

Steve Whitman, chief epidemiologist for the City of

Chicago, presents a key map showing communities

with high poverty rates, with an overlay showing

where heat-related deaths occurred.

The mayor creates a task force and an emergency

plan, but the plan does not address the issue of

poverty or the social fau

lt lines that leave some

neighborhoods at the mercy of the heat wave.

Whitman says what is needed is “a social evil

remedying plan.”

The slow motion disaster

(21:53–24:45)

Police tell children to “back off”

as they shut down the spray

from a hydrant. Meanwhile,

across town by the lakeshore,

the Buckingham Fountain puts

on a spectacular display. Author

Eric Klinenberg worries about

the collective failure to address

these everyday crises, calling

them “disasters in slow motion.”

The aftermath of Hurricane

Katrina in New Orleans provides

further evidence of systemic

denial and neglect.

The discussion pivots to

uncomfortable topics, including

the impact of generations of

racism and denial. The recovery

plan for New Orleans, with its

focus on physical repairs to the

dikes, is an example.

The impact of entrenched racism and denial

(24:46 – 35:45)

In Chicago, the mayor’s climate action plan will develop a “green roof”

for city hall. In South Chicago, community organizer Orrin Williams

laments the continued erosion of a once-vibrant and safe

neighborhood after it was cut off by redlining by the banks.

With gradual disinvestment, he says, communities were

“left out” and “forgotten.”

Chicago epidemiologist Steve Whitman demonstrates that the

differences between Black and white communities in measures of

health are growing. Life expectancy in Black communities is 65 years.

For whites, it is 81 years. Whitman goes on to say that 3,200 people

die in Chicago from health inequities due to racism every year.

If the same number of people died from terrorism, Helfand suggests,

it would be a national tragedy; but dying predictably, from readily

treatable diseases, is not treated as

a disaster.

2. What does Klinenberg mean when he says natural disasters are

more “seen” and visible? Why is it different for unnatural disasters

that are man-made? (04:08–05:15)

3. How does Alberta Washington’s fate resemble those of several

others who perished in the heat wave?

(06:38–07:40, 15:37–16:20)

4. There was a media frenzy related to the heat wave in 1995 in

Chicago. What did the media focus on at the time, and what was

the underreported story? (10:54–11:22)

5. What is problematic in the mayor’s statement that “all neighbor-

hoods were impacted by the heat wave”? What is Klinenberg’s

opinion on that? (19:26–20:21)

6. What was the “heat emergency plan”? Why did epidemiologist

Steve Whitman lack confidence in it? (20:31–21:52)

7. What does Klinenberg mean when he says he is “concerned with

the collective failure to address the everyday crisis, the disaster

in slow motion”? (22:37–23:25)

8. Following the discussion of Hurricane Katrina and its impact on

New Orleans, the focus of the documentary shifts to an examina-

tion of the impact of generations of racism and denial. Why is this

a pivotal moment for the filmmaker and the film? (23:35–24:45)

9. How did the practices of redlining and contract buying exploit

families of color and affect their neighborhoods? (27:41–32:14)

10. Using Steve Whitman’s research findings, how would you describe

a Black neighborhood and the people’s living conditions?

(32:15–35:00) See also Whitman, Steve (2010),

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in Chicago.

11. Note the variety of maps and overlays shown in the film. How do

maps help us examine the health risk factors for African Americans

and their relative vulnerability? Why does the map of heat deaths

overlap with other demographic indicators? Discuss. (32:15–35:00)

12. Disaster preparedness is a well-funded industry. Explain.

(35:10–43:35)

13. What is the difference between a disaster kit and a “get through

the week” kit?

14. How do organizations like Sinai Urban Health Institute and Grow-

ing Home organic farm provide a sign of hope? (45:10–50:05)

15. How would an expanded definition of disaster help in realigning

national priorities? (52:14–53:40)

3,200 people die from

racism each year.

Steve Whitman, epidemiologist

Disaster-prevention/preparedness (35:45–45:12)

Judith Helfand attends disaster preparedness exercises in Cook County

and in Kentucky, two of many exercises in a rapidly expanding national

industry. Helfand finds expensive resources standing by in preparation

for fire, earthquakes, or floods. Could these resources instead be