Page 1 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

Medical Coverage Policy

Effective Date .................... 8/15/2024

Next Review Date .............. 8/15/2025

Coverage Policy Number ............. 0152

Breast Reduction

Table of Contents

Overview ............................................ 2

Coverage Policy .................................... 2

Health Equity Considerations .................. 3

General Background ............................. 3

Medicare Coverage Determinations ......... 7

Appendix ............................................. 7

Coding Information ............................... 8

References .......................................... 9

Revision Details ................................. 12

Related Coverage Resources

Acupuncture

Breast Reconstruction following Mastectomy or

Lumpectomy

Chiropractic Care

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Physical Therapy

Gynecomastia Surgery

Gender Dysphoria Treatment

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE

The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies.

Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients

and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and

coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide

guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please

note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement,

Evidence of Coverage, Certificate of Coverage, Summary Plan Description (SPD) or similar plan

document] may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which these Coverage

Policies are based. For example, a customer’s benefit plan document may contain a specific

exclusion related to a topic addressed in a Coverage Policy. In the event of a conflict, a customer’s

benefit plan document always supersedes the information in the Coverage Policies. In the absence

of a controlling federal or state coverage mandate, benefits are ultimately determined by the

terms of the applicable benefit plan document. Coverage determinations in each specific instance

require consideration of 1) the terms of the applicable benefit plan document in effect on the date

of service; 2) any applicable laws/regulations; 3) any relevant collateral source materials including

Coverage Policies and; 4) the specific facts of the particular situation. Each coverage request

should be reviewed on its own merits. Medical directors are expected to exercise clinical judgment

where appropriate and have discretion in making individual coverage determinations. Where

coverage for care or services does not depend on specific circumstances, reimbursement will only

be provided if a requested service(s) is submitted in accordance with the relevant criteria outlined

in the applicable Coverage Policy, including covered diagnosis and/or procedure code(s).

Reimbursement is not allowed for services when billed for conditions or diagnoses that are not

covered under this Coverage Policy (see “Coding Information” below). When billing, providers

must use the most appropriate codes as of the effective date of the submission. Claims submitted

Page 2 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

for services that are not accompanied by covered code(s) under the applicable Coverage Policy

will be denied as not covered. Coverage Policies relate exclusively to the administration of health

benefit plans. Coverage Policies are not recommendations for treatment and should never be used

as treatment guidelines. In certain markets, delegated vendor guidelines may be used to support

medical necessity and other coverage determinations.

Overview

This Coverage Policy addresses breast reduction for symptomatic macromastia and breast

reduction surgery on the nondiseased/contralateral breast following a mastectomy or lumpectomy.

Coverage Policy

Coverage for breast reduction varies across plans. Please refer to the customer’s benefit

plan document for coverage details.

Breast reduction surgery on the nondiseased/contralateral breast when performed to

produce a symmetrical appearance following a mastectomy or lumpectomy is

considered medically necessary.

If coverage for breast reduction is available, the following conditions of coverage apply.

Breast reduction is considered medically necessary for the treatment of macromastia

(i.e., large breasts) in women at least 18 years of age, or with completed breast growth,

when ALL the following criteria are met:

• macromastia is causing at least ONE of the following conditions/symptoms that has been

unresponsive to medical management:

shoulder, upper back/ neck pain, and/or ulnar nerve palsy for which no other

etiology has been found on appropriate evaluation

intertrigo, dermatitis, eczema, or hidradenitis at the inframammary fold

• preoperative photographs confirm the presence of:

significant breast hypertrophy

shoulder grooving from bra straps and/or intertrigo (if stated to be present)

• average grams of tissue to be removed per breast are above the 22nd percentile on the

Schnur Sliding Scale (see Appendix A) based on the individual's body surface area (BSA) or

regardless of BSA, more than 1 kg of breast tissue will be removed per breast

Breast reduction or mastopexy prior to mastectomy is considered medically necessary

when a staged procedure is planned prior to a nipple-sparing mastectomy.

Note: The following are considered integral to breast reduction (CPT

®

code 19318) and

not separately reimbursable:

• Nipple and areola reconstruction (CPT

®

code 19350)

• Suction lipectomy or ultrasonically-assisted suction lipectomy (liposuction) (CPT

®

code 15877)

Breast reduction for either of the following indications is considered cosmetic in nature

and not medically necessary:

Page 3 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

• surgery is being performed to treat psychological symptomatology or psychosocial

complaints, in the absence of significant physical findings that meet the above listed

criteria

• surgery is being performed for the sole purpose of improving appearance

Correction of benign inverted nipples (CPT

®

code 19355) is considered cosmetic in

nature and not medically necessary.

Suction lipectomy or ultrasonically-assisted suction lipectomy (liposuction) as a sole

method of treatment for symptomatic macromastia is considered unproven.

Health Equity Considerations

Health equity is the highest level of health for all people; health inequity is the avoidable

difference in health status or distribution of health resources due to the social conditions in which

people are born, grow, live, work, and age.

Social determinants of health are the conditions in the environment that affect a wide range of

health, functioning, and quality of life outcomes and risks. Examples include safe housing,

transportation, and neighborhoods; racism, discrimination and violence; education, job

opportunities and income; access to nutritious foods and physical activity opportunities; access to

clean air and water; and language and literacy skills.

Sociodemographic and economic disparities have a role in outcomes related to breast reduction.

In a retrospective observational study of 414 women who underwent inpatient bilateral reduction

mamamoplasty, comorbidity, age, race, payor status and rural- urban density were evaluated for

risk of post op complications. Higher comorbidity index (p<0.001), Black race (p<0.001) and

treatment within a nonmetropolitan or rural county (p=0.0017) were significant predictors of

increased risk of postoperative complication. Age, comorbidity severity, race and zip code income

quartile were also evaluated for risk of extended length of stay. Older age (p= 0.0078), increased

comorbidity severity (p< 0.001) and Black race (p= 0.0011) predicted higher risk of extended

length of stay, whereas Hispanic race predicted decrease of such risk (p< 0.001) (Kim and

Ascherman, 2024).

General Background

Macromastia (i.e., female breast hypertrophy) is the development of abnormally large breasts.

Normal breast development begins at approximately five weeks’ gestation and continues until a

woman is in her early twenties, with the rate of development and degree of asymmetry often

varying. Spontaneous massive growth of the breasts during puberty and adolescence is thought to

be the result of excessive end-organ sensitivity to gonadal hormones. It is more commonly

bilateral, often occurs over a brief period, and most commonly affects adolescent girls.

Management is individualized and may range from reassurance or the use of supportive

brassieres. It is recommended that surgery be delayed until late adolescence to allow complete

breast development (Conner and Merritt, 2020; McGrath and Pomerantz, 2012).

The presence of macromastia may cause clinical manifestations when the excessive breast weight

adversely affects the supporting structures of the shoulders, neck, and trunk. Increased weight on

the shoulders can cause pain, fatigue in the cervical and thoracic spine, which can lead to poor

posture, thoracic kyphosis and occipital headaches. Grooving or ulceration of the skin on the

shoulders, pressure on the brachial plexus causing neurological symptoms in the arms and skin

conditions occurring at the inframammary fold such as intertrigo, dermatitis, eczema, or

Page 4 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

hidradenitis (inflammation of the apocrine sweat glands resulting in obstruction of the ducts) may

also exist. The presence of these persistent signs and painful symptoms distinguishes

macromastia from large, normal breasts and may prompt the need for surgical intervention

(American Society of Plastic Surgeons [ASPS], 2011/2021; McGrath and Pomerantz, 2012;

Schnur, et al., 1997).

Medical management of conditions/symptoms may include any of the following: weight loss;

acupuncture; massage therapy; chiropractic treatment; adequate bra support (proper fit and wide

strap support); nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)/analgesia; and physical therapy,

when a functional impairment exists (Hansen and Chang, 2023; Collins, et al., 2002).

Reduction mammoplasty is the surgical excision of a substantial portion of the breast, including

the skin and the underlying glandular tissue, until a clinically normal size is obtained. Relocation of

the nipple, which may result in decreased sensation and altered lactation, may also be required

during this procedure. Therefore, it has been recommended that surgery should not be performed

on an individual until the breasts are fully developed. Complications range from mild to severe and

may be early or late. The most common early complication independent of reduction technique is

delayed wound healing. Late complications can include, but are not limited to, seroma, scars and

pseudoptosis. A BMI ≥30 kg/m

2

and smoking may increase the risk of complications. Persons who

are obese or irradiated are more likely to develop infections, and smokers experienced a higher

incidence of wound dehiscence than did nonsmokers (Zhang, et al., 2016; McGrath and

Pomerantz, 2012; Nahai, et al., 2008; Greydanus, et al., 2006).

Amaral et al. (2011) reported on racial and socioeconomic disparities in reduction mammoplasty.

Their analysis of the 2007 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database for differences in race and payer

mix revealed that Black and Hispanic patients (p<0.0001) were more likely to undergo reduction

mammoplasty.

The available techniques for breast reduction differ according to the pattern of skin resection, as

well as the method for removing breast tissue and moving the nipple. Factors identified on the

preoperative breast evaluation that are used for determining the best approach include

preoperative breast size and degree of ptosis, desired postoperative breast size, skin quality, and

a history of prior breast surgery. Liposuction for conturing to remove excess fat in the lateral area

of the breast at the time of surgery is considered part of the breast reduction procedure (Pu,

2021; Cohen, 2018). Among these, preoperative breast size and estimated breast reduction

volume are the most important factors influencing the technique selected. Generally, breast

hypertrophy is stratified according to the estimated volume to be resected:

• small reductions remove 200 to 400 grams per side

• moderate reductions remove 400 to 700 grams per side

• large reductions remove 700 to 1200 grams per side

• reductions in patients with gigantomastia involve massive reductions of more than 1200

grams per side

Several methods are available to help surgeons estimate breast resection volumes. The two most

common methods are the Schnur sliding scale and the Descamps formula. The Schnur sliding

scale estimates resection weight based on the patient's body surface area. The Descamps method

estimates resection volume based on a regression analysis (Hansen and Chang, 2023). There is no

consensus on which formula to use to calculate body surface area (Redlarski, et. al., 2016).

The Schnur Sliding Scale is an evaluation tool that may be used to determine the appropriate

amount of tissue to be removed compared to a patient’s total body surface area (BSA). This can

be instrumental in determining if breast reduction is being planned for a purely cosmetic reason or

as a medically necessary procedure. In a survey of plastic surgeons, Schnur et al. (1991)

Page 5 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

concluded that women whose removed breast weight was less than the 5th percentile sought the

procedure for cosmetic reasons and all women whose breast weight was greater than the 22nd

percentile sought the procedure for medical reasons. One way to calculate the BSA is: BSA (in m

2

)

= [height (cm)]

0.718

X [weight (kilograms [kg])]

0.427

X .007449.

Generally, most patients do not require hospitalization after breast reduction surgery. An

overnight stay with observation may be necessary for some women with medical comorbidities.

Patients who experience severe postoperative nausea and vomiting may require extended

observation or admission for intravenous fluid therapy and antiemetics (Hansen and Chang,

2023).

Breast tissue regrowth following initial breast reduction in adolescence has been reported

(Greydanus, et al., 2006). The growth of the female breast is generally described by five stages

referred to as Tanner stages or sexually maturity rating (SMR) stages. A number of clinical

correlations are noted with the SMR stages, including the timing of breast reduction at stage V

(i.e., mature stage) (DeSilva, et al., 2006). In a review of elective plastic surgical procedures in

adolescence, McGrath and Schooler (2004) stated “Breast development is variable but usually

plateaus at 15–16 years of age. Reduction mammoplasty is postponed until breast maturity is

reached. Occasionally, surgery is considered earlier when severe symptoms are encountered;

there is a risk of recurrent hypertrophy, however.” In general, breast maturity should have been

reached prior to considering breast reduction surgery.

Staged breast reduction in patients with large and ptotic breasts has been shown to decrease

rates of major flap necrosis before nipple-sparing mastectomy and preserve the viability of the

nipple. Classification of breast ptosis (Regnault, 1976) is based on the relationship of the nipple to

the inframammary fold (IMF). In mild, or Grade I ptosis, the nipple is situated within 1 cm of the

inframammary fold and is above the lower pole of the breast. In moderate, or Grade II ptosis, the

nipple is 1–3 cm below the inframammary fold but is still located above the lowest point of the

breast. In severe, or grade III ptosis, the nipple is more than 3 cm below the inframammary fold

and is situated at the lowest part of the breast. Studies are primarily in the form of case series

and retrospective reviews with small patient populations (Tondu, 2022; Economides et al., 2019;

Saliban et al., 2019; Gunnarsson et al., 2017; Spear et al., 2012). Spear et al. (2012) first

described the procedure in a case series of 15 patients (24 breasts) who underwent nipple-sparing

mastectomy after mastopexy or reduction. Complications occurred in four (17%) of the 24 breasts

including skin flap necrosis (n=2 breasts), minimal partial nipple-areola complex necrosis (n=3

breasts) and an expander explanted for infection related to skin flap necrosis (n=1 breast).

Successful nipple-sparing mastectomy and prior mastopexy or reduction (without residual effects

of the nipple-areola complex or skin flap necrosis) occurred in 14 patients (23 breasts, 96%).

Nipple inversion or retraction is when the nipple is pulled in and points inward instead of out. It

can affect one breast or both and can be acquired or congenital. The cause of acquired nipple

inversion can be due to benign or malignant causes. Congenital nipple inversion is usually bilateral

and is benign (Killelea and Sowden, 2024). Correction of nipple inversion is considered cosmetic in

nature and not medically indicated.

Literature Review

Controlled clinical studies assessing the effectiveness of surgical removal of modest amounts of

breast tissue in reducing neck, shoulder, and back pain and related disabilities in women are

lacking. Despite the lack of controlled studies, reduction mammoplasty has become the standard

of care for a subset of individuals with symptomatic macromastia. Evidence suggests that

calculating breast reduction in correlation to each patient’s body weight and height can have an

effect on reducing preoperative signs and persistent physical conditions. (Cunningham, et al.,

Page 6 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

2005; Blomqvist, et al., 2004; Souto, et al., 2003; Collins, et al., 2002; Ayhan, et al., 2002;

Bruhlmann, et al., 1998).

Chadbourne et al. (2001) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 29 studies of 4173

patients to determine whether reduction mammoplasty improves measurable outcomes in women

with breast hypertrophy. Experimental and observational studies were included; no randomized

controlled trials were found. Outcomes assessed were postoperative physical signs and symptoms

such as shoulder pain, shoulder (bra strap) grooving, and quality-of-life domains, such as physical

and psychological functioning, and were expressed primarily as risk differences. The mean body

mass index of the patients was 27.5 kg/m

2

in the observational studies and 29.6 kg/m

2

in the

experimental studies. The average tissue mass removed per breast was approximately 1400

grams. The authors concluded that reduction mammoplasty was associated with a statistically

significant improvement in physical signs and symptoms involving shoulder pain, shoulder

grooving, upper/lower back pain, neck pain, intertrigo, breast pain, headache, and pain/numbness

in the hands. The quality-of-life parameter of physical functioning was also statistically significant,

while psychological functioning was not significant. The evidence suggests that women undergoing

reduction mammoplasty for breast hypertrophy have significant postoperative improvement in

preoperative signs and symptoms, quality of life, or both.

Breast Reduction by Liposuction

Suction lipectomy or ultrasonically assisted suction lipectomy (liposuction) as a sole procedure has

been introduced as an alternative method in reducing breast size. The effectiveness of liposuction,

in terms of removing glandular breast tissue, rather than fatty tissue in the breast, remains to be

demonstrated. Evidence supporting the effects of this approach on patient outcomes has been

limited to retrospective/prospective uncontrolled studies and case series, and there are minimal

long-term data comparing this technique to the standard surgical approach (Moskovitz, et al.,

2007; Sadove, et al., 2005).

Professional Societies/Organizations

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): In a Committee Opinion

(2017, reaffirmed 2020), ACOG recognizes that breast reduction surgery in adolescents with large

breasts can relieve back, shoulder, and neck pain. Recommendations for timing of surgery include

postponing surgery until breast maturity is reached, waiting until there is stability in cup size over

6 months, and waiting until the age of 18 years. The committee states that the timing may be

reasonably determined by the severity of symptoms. It is also recommended that an assessment

of the adolescent’s emotional, physiologic, and physical maturity be conducted.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS): In 2022, the American Society of Plastic

Surgeons convened a multidisciplinary work group consisting of members of the American Society

of Plastic Surgeons, the American Society of Breast Surgeons, the American Physical Therapy

Association, and a patient representative to revise the 2012 guidelines for reduction

mammaplasty. After evaluating the evidence-based literature, the work group made the following

recommendations with level of evidence and strength of recommendation (Perdikis, et al., 2022):

• post-menarche female patients presenting with breast hypertrophy should be offered

reduction mammaplasty surgery as first-line therapy over non-operative therapy based

solely on the presence of multiple symptoms rather than resection weight (high evidence

quality, strong recommendation)

• clinicians should counsel post-menarche patients with symptomatic breast hypertrophy

considering reduction mammaplasty that they may have a higher risk of complications if

they are older than 50 years old, have a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m

2

, or

require chronic corticosteroid use (all independent variables) (moderate evidence quality,

moderate recommendation)

Page 7 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

The 2011 update (reaffirmed 2021) to the 2002 ASPS policy statement, insurance coverage

criteria for third-party payors for reduction mammaplasty, recommends that justification for

reduction mammaplasty should be based on the probability of relieving the clinical signs and

symptoms of macromastia, not the degree of breast hypertrophy present (cup size or amount of

tissue removed). Symptomatic breast hypertrophy is defined as a syndrome of persistent neck

and shoulder pain, painful shoulder grooving from brassiere straps, chronic intertriginous rash of

the inframammary fold, and frequent episodes of headache, backache, and neuropathies caused

by heavy breasts caused by an increase in the volume and weight of breast tissue beyond normal

proportions. These policy recommendations are based on the 2011 ASPS evidence-based

companion guideline for Reduction Mammaplasty.

Medicare Coverage Determinations

Contractor

Determination Name/Number

Revision Effective

Date

NCD

National

No Determination found

LCD

National Government

Services, Inc.

Reduction Mammaplasty/L35001

11/07/2019

LCD

Noridian

Plastic Surgery/L35163 and L37020

10/01/2019

Note: Please review the current Medicare Policy for the most up-to-date information.

(NCD = National Coverage Determination; LCD = Local Coverage Determination)

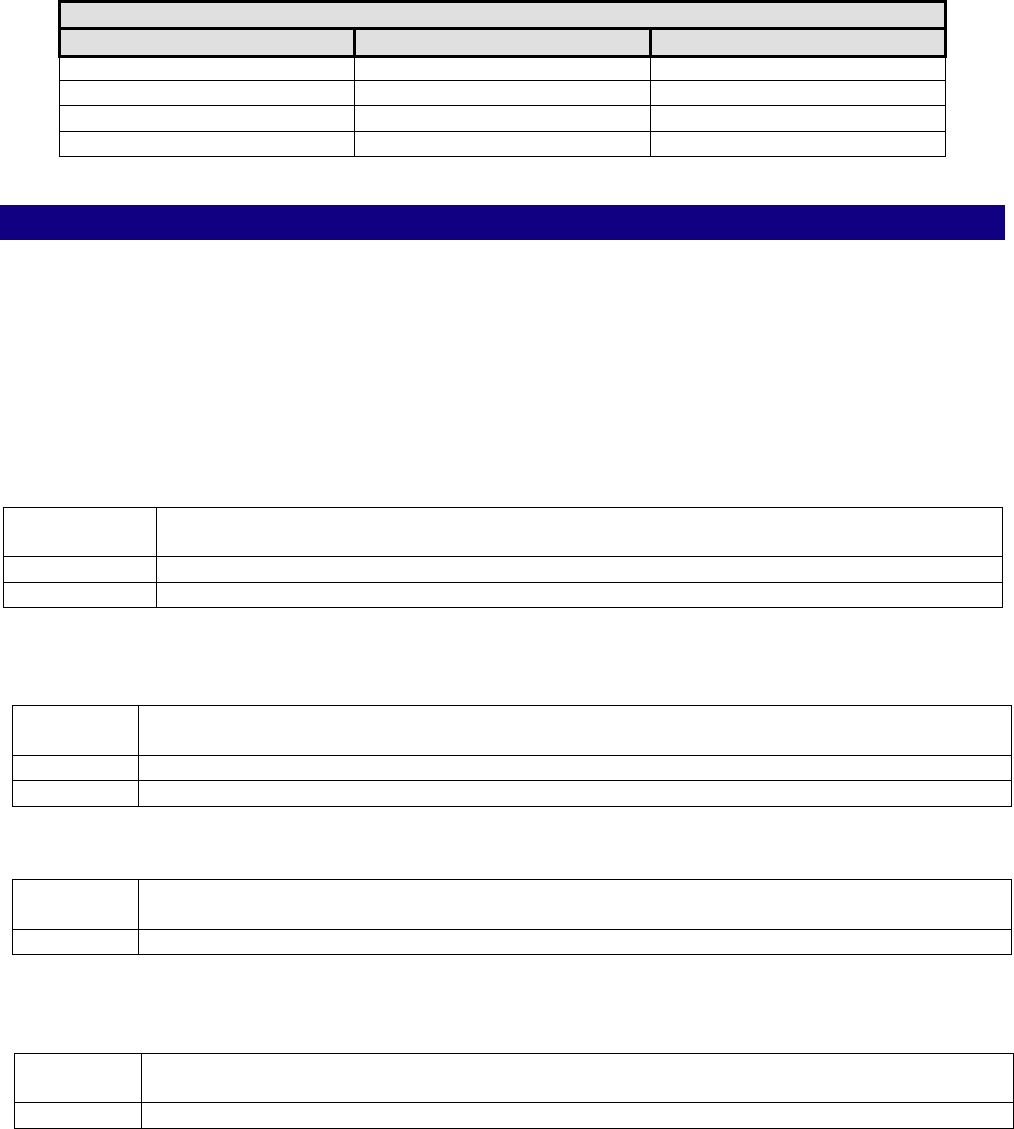

Appendix

Schnur Sliding Scale

Body Surface Area and Cutoff Weight of Breast Tissue Removed

Breast Reduction (gm)

Body Surface Area (m

2

)

Lower 5%

Lower 22%

1.35

127

199

1.40

139

218

1.45

152

238

1.50

166

260

1.55

181

284

1.60

198

310

1.65

216

338

1.70

236

370

1.75

258

404

1.80

282

441

1.85

308

482

1.90

336

527

1.95

367

575

2.00

401

628

2.05

439

687

2.10

479

750

2.15

523

819

2.20

572

895

2.25

625

978

2.30

682

1068

2.35

745

1167

Page 8 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

Breast Reduction (gm)

Body Surface Area (m

2

)

Lower 5%

Lower 22%

2.40

814

1275

2.45

890

1393

2.50

972

1522

2.55

1062

1662

Schnur Sliding Scale (Schnur, et al., 1991)

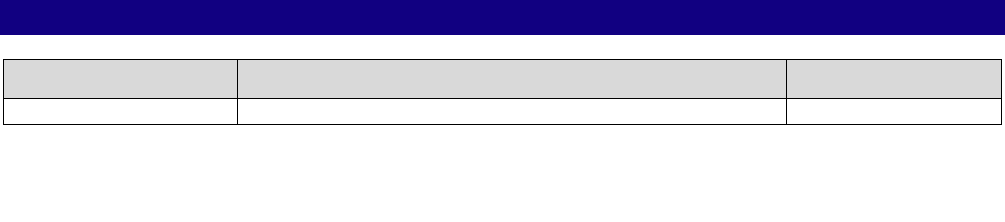

Coding Information

Notes:

1. This list of codes may not be all-inclusive since the American Medical Association (AMA)

and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) code updates may occur more

frequently than policy updates.

2. Deleted codes and codes which are not effective at the time the service is rendered may

not be eligible for reimbursement.

Considered Medically Necessary when criteria in the applicable policy statements listed

above are met:

CPT

®

*

Codes

Description

19316

Mastopexy

19318

Breast reduction

Considered integral to and not separately reimbursed when performed with a Medically

Necessary breast reduction:

CPT

®

*

Codes

Description

15877

Suction assisted lipectomy; trunk

19350

Nipple/areola reconstruction

Considered Cosmetic/Not Medically Necessary:

CPT

®

*

Codes

Description

19355

Correction of inverted nipples

Considered Unproven when performed as a sole method of treatment for symptomatic

macromastia:

CPT

®

*

Codes

Description

15877

Suction assisted lipectomy; trunk

*Current Procedural Terminology (CPT

®

) ©2023 American Medical Association: Chicago,

IL.

Page 9 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

References

1. Amaral MH, Dao H, Shin JH. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in reduction

mammoplasty: an analysis of nationwide inpatient sample database. Ann Plast Surg. 2011

May;66(5):476-8. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182185efa. PMID: 21451367.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Committee Opinion No. 686:

Breast and Labial Surgery in Adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan;129(1):e17-e19. doi:

10.1097/AOG.0000000000001862. PMID: 28002312.

3. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Reduction Mammaplasty Recommended

Insurance Coverage for Third-Party Payer Coverage. May 2011. Updated Reaffirmed: Mar

2021. Accessed Jul 9, 2024. Available at URL address: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-

medical-professionals/health-policy/recommended-insurance-coverage-criteria

4. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Reconstructive Procedures: Breast Reduction,

Reduction Mammaplasty. 2023. Accessed Jun 27, 2023. Available at URL address:

https://www.plasticsurgery.org/reconstructive-procedures/breast-reduction

5. Ayhan S, Basterzi Y, Yavuzer R, Latifoglu O, Cenetoglu S, Atabay K, Celebi MC. Histologic

profiles of breast reduction specimens. Anesthetic Plast Surg. 2002 May;26(3):203-5.

6. Banikarim C, DeSilva N. Breast disorders in children and adolescents. In: UpToDate, Drutz

JE and Middleman AB (Eds.). Feb 10, 2022. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. Accessed Jun 27,

2023.

7. Bellini E, Grieco MP, Raposio E. A journey through liposuction and liposculture: Review. Ann

Med Surg (Lond). 2017 Nov 6;24:53-60.

8. Blomqvist L, Brandberg Y. Three-year follow-up on clinical symptoms and health-related

quality of life after reduction mammaplasty Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Jul;114(1):49-54.

9. Bruhlmann Y, Tschopp H. Breast reduction improves symptoms of macromastia and has a

long-lasting effect. Ann Plast Surg. 1998 Sep;41(3):240-5.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs)

alphabetical index. Accessed Jun 27, 2023. Available at URL address:

https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/reports/local-coverage-final-lcds-

alphabetical-report.aspx?lcdStatus=all

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). National Coverage Determinations

(NCDs) alphabetical index. Accessed Jun 27, 2023. Available at URL address:

https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/reports/national-coverage-ncd-

report.aspx?chapter=all&sortBy=title

12. Chadbourne EB, Zhang S, Gordon MJ, Ro EY, Ross SD, Schnur PL, Schneider-Redden PR.

Clinical outcomes in reduction mammoplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

published studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001 May;76(5):503-10.

13. Chao JD, Memmel HC, Redding JF, Egan L, Odom LC, Casas LA. Reduction mammaplasty is

a functional operation, improving quality of life in symptomatic women: a prospective,

Page 10 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

single-center breast reduction outcome study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Dec;110(7):1644-

52.

14. Cohen R. Mastopexy options and techniques. Nahabedian MY, editor. In: Plastic Surgery,

Volume 5: Breast, 4

th

ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018. Ch 6, 87-107.e1

15. Collins ED, Kerrigan CL, Kim M. The effectiveness of surgical and nonsurgical interventions

in relieving the symptoms of macromastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Jul;109:1556-66.

16. Conner LN, Merritt DF. Breast Concerns. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St Geme JW, Schor

NF, Behrman RE, editors. Kliegman: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21

th

ed. Philadelphia,

PA: Elsevier; 2020. Ch 556, Breast Concerns, 2853-57.

17. Cunningham BL, Gear AJ, Kerrigan CL, Collins ED. Analysis of breast reduction

complications derived from the BRAVO study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005 May;115(6):1597-

604.

18. DeSilva NK, Brandt ML. Disorders of the breast in children and adolescents, Part 1:

Disorders of growth and infections of the breast. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006

Oct;19(5):345-9.

19. Economides JM, Graziano F, Tousimis E, Willey S, Pittman TA. Expanded Algorithm and

Updated Experience with Breast Reconstruction Using a Staged Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

following Mastopexy or Reduction Mammaplasty in the Large or Ptotic Breast. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2019 Apr;143(4):688e-697e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005425.

Erratum in: Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Jun;143(6):1810-1811. PMID: 30921113.

20. Gonzalez MA, Glickman LT, Aladegbami B, Simpson RL. Quality of life after breast reduction

surgery: a 10-year retrospective analysis using the Breast Q questionnaire: does breast

size matter? Ann Plast Surg. 2012 Oct;69(4):361-3.

21. Greydanus DE, Matytsina L, Gains M. Breast Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Prim

Care. 2006 Jun;33(2):455-502.

22. Gunnarsson GL, Bille C, Reitsma LC, Wamberg P, Thomsen JB. Prophylactic Nipple-Sparing

Mastectomy and Direct-to-Implant Reconstruction of the Large and Ptotic Breast: Is

Preshaping of the Challenging Breast a Key to Success? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017

Sep;140(3):449-454. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003621. PMID: 28841601.

23. Hansen J, Chang S. Overview of breast reduction. In: UpToDate, Chagpar AB, Colwell AS

(Ed). Last updated Apr 19, 2023. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. Accessed Jul 9, 2024.

24. Haug V, Kadakia N, Wang AT, Dorante MI, Panayi AC, Kauke-Navarro M, Hundeshagen G,

Diehm YF, Fischer S, Hirche C, Kneser U, Pomahac B. Racial disparities in short-term

outcomes after breast reduction surgery-A National Surgical Quality Improvement Project

Analysis with 23,268 patients using Propensity Score Matching. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet

Surg. 2022 Jun;75(6):1849-1857. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.01.001. Epub 2022 Jan 16.

PMID: 35131191.

25. Jakubietz RG, Jakubietz DF, Gruenert JG, Schmidt K, Meffert RH, Jakubietz MG. Breast

reduction by liposuction in females. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011 Jun;35(3):402-7.

Page 11 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

26. Kalliainen LK; ASPS Health Policy Committee. ASPS clinical practice guideline summary on

reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Oct;130(4):785-9.

27. Killelea B and Sowden M. Nipple inversion. In: UpToDate, Chen W, ed. Feb 7, 2024.

UpToDate, Walthem, MA. Accessed Jul 9, 2024.

28. Kim DK, Ascherman JA. Impact of Sociodemographic and Hospital Factors on Inpatient

Bilateral Reduction Mammaplasty: A National Inpatient Sample Analysis. Plast Reconstr

Surg Glob Open. 2024 Mar 22;12(3):e5682.

29. Kocak E, Carruthers KH, McMahan JD. A reliable method for the preoperative estimation of

tissue to be removed during reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011

Mar;127(3):1059-64.

30. Manahan MA, Buretta KJ, Chang D, Mithani SK, Mallalieu J, Shermak MA. An outcomes

analysis of 2142 breast reduction procedures. Ann Plast Surg. 2015 Mar;74(3):289-92.

31. McGrath MH, Pomerantz J. Plastic Surgery. Reduction Mammoplasty. In: Townsend CM,

Beuchamp RD, Evers BM, editors. Townsend: Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 19

th

ed.

Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company. 2012. pg 1932-33. Ch 69.

32. McGrath MH, Schooler WG. Elective plastic surgical procedures in adolescence. Adolesc Med

Clin. 2004 Oct;15(3):487-502.

33. Morris MP, Christopher AN, Patel V, Broach RB, Fischer JP, Butler PD. Assessing Disparities

in Reduction Mammaplasty: There Is Room for Improvement. Aesthet Surg J. 2021 Jun

14;41(7):NP796-NP803. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab138. PMID: 33735387.

34. Moskovitz MJ, Baxt SA, Jain AK, Hausman RE. Liposuction breast reduction: a prospective

trial in African American women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Feb;119(2):718-26; discussion

727-8.

35. Nahai FR, Nahai F. MOC-PSSM CME article: Breast reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008

Jan;121(1 Suppl):1-13.

36. National Comprehensive Cancer Network

®

(NCCN). NCCN GUIDELINES™ Clinical Practice

Guidelines in Oncology

™

.

©

Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. Version 2.2024 Mar 11, 2024.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2024, All Rights Reserved. Accessed Jul 9,

2024. Available at URL address:

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_risk.pdf

37. National Comprehensive Cancer Network

®

(NCCN). NCCN GUIDELINES™ Clinical Practice

Guidelines in Oncology

™

. Genetic/Familial High-risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and

Pancreatic. Version 3.2024 Feb 12, 2024. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.

2022, All Rights Reserved. Accessed Jul 9, 2024. Available at URL address:

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf

38. Perdikis G, Dillingham C, Boukovalas S, Ogunleye AA, Casambre F, Dal Cin A, Davidson C,

Davies CC, Donnelly KC, Fischer JP, Johnson DJ, Labow BI, Maasarani S, Mullen K, Reiland

J, Rohde C, Slezak S, Taylor A, Visvabharathy V, Yoon-Schwartz D. American Society of

Plastic Surgeons Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline Revision: Reduction

Mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022 Mar 1;149(3):392e-409e. doi:

10.1097/PRS.0000000000008860. PMID: 35006204.

Page 12 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

39. Pu LLQ. Breast Reduction—Medial Pedicle Technique. Pu LLQ and Jewell ML, eds. In: Atlas

of Contemporary Aesthetic Breast Surgery, Elsevier Inc. 2021. Ch 18, 249-258.

40. Redlarski G, Palkowski A, Krawczuk M. Body surface area formulae: an alarming ambiguity.

Sci Rep. 2016 Jun 21;6:27966. doi: 10.1038/srep27966. PMID: 27323883; PMCID:

PMC4914842.

41. Regnault P. Breast ptosis. Definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976 Apr;3(2):193-

203. PMID: 1261176.

42. Sadove R. New observations in liposuction-only breast reduction. Aesthetic Plast Surg.

2005 Jan-Feb;29(1):28-31.

43. Salibian AA, Frey JD, Karp NS, Choi M. Does Staged Breast Reduction before Nipple-

Sparing Mastectomy Decrease Complications? A Matched Cohort Study between Staged

and Nonstaged Techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Nov;144(5):1023-1032. doi:

10.1097/PRS.0000000000006121. PMID: 31373992.

44. Schnur PL, Hoehn JG, Ilstrup DM, Cahoy MJ, Chu CP. Reduction mammaplasty: cosmetic or

reconstructive procedure? Ann Plast Surg. 1991 Sep;27(3):232-7.

45. Schnur PL, Schnur DP, Petty PM, Hanson TJ, Weaver Al. Reduction mammoplasty: an

outcome study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Sep;100(4):875-83.

46. Singh KA, Losken A. Additional benefits of reduction mammaplasty: a systematic review of

the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Mar;129(3):562-70.

47. Souto GC, Giugliani ER, Giugliani C, Schneider MA. The impact of breast reduction surgery

on breastfeeding performance. J Hum Lact. 2003 Feb;19(1):43-9;quiz 66-9, 120.

48. Spear SL, Rottman SJ, Seiboth LA, Hannan CM. Breast reconstruction using a staged

nipple-sparing mastectomy following mastopexy or reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012

Mar;129(3):572-581. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318241285c. PMID: 22373964.

49. Tondu T, Thiessen F, Hubens G, Tjalma W, Blondeel P, Verhoeven V. Delayed two-stage

nipple sparing mastectomy and simultaneous expander-to-implant reconstruction of the

large and ptotic breast. Gland Surg. 2022 Mar;11(3):524-534. doi: 10.21037/gs-21-734.

PMID: 35402205; PMCID: PMC8984988.

50. Zhang MX, Chen CY, Fang QQ, Xu JH, Wang XF, Shi BH, Wu LH, Tan WQ. Risk Factors for

Complications after Reduction Mammoplasty: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Dec

9;11(12):e0167746.

Revision Details

Type of Revision

Summary of Changes

Date

Annual review

• No clinical policy statement changes

8/15/2024

Page 13 of 13

Medical Coverage Policy: 0152

“Cigna Companies” refers to operating subsidiaries of The Cigna Group. All products and services

are provided exclusively by or through such operating subsidiaries, including Cigna Health and Life

Insurance Company, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company, Evernorth Behavioral Health,

Inc., Cigna Health Management, Inc., and HMO or service company subsidiaries of The Cigna

Group. © 2024 The Cigna Group.